The Stewarts of Leeds - One Family's Experience of War and Loss

Close to the New Adel Lane boundary of the 1910 extension to Lawnswood Cemetery, in Leeds, stands a pristine, white headstone dedicated to the Stewart family. Recorded in lead lettering is a roll call of the five Stewart brothers who died because of their service during the Great War. The gravestone tells only a part of the story of the grave beneath it. Of the brothers listed on the headstone, only Leonard is buried here, and the inscriptions for the other brothers are memorials to them. As well as Leonard, the father of the family, James Frederick Stewart is buried in this plot, as are the eldest son of the family, James Frederick Patrick Stewart, and the only daughter in the family, Ivy Louise, who married Albert Edward Scholey. All are remembered by additional inscriptions on the stone, except James Frederick Patrick Stewart, whose name has not been added.

The headstone marking the Stewart Family plot in Lawnswood Cemetery, Leeds

It has long been accepted that the loss of the five Stewart brothers was the heaviest loss of any family from Leeds during the war, and because of that, the story of the brothers who died has featured in several Remembrance projects and news items in recent years, but almost nothing has been written about the brothers who survived the war. This can be partially explained by the fact that, until relatively recently, it has been more difficult to research a survivor of the Great War than it was to research someone who died. That imbalance has largely been removed with the advent of online access to many sets of records which had previously required an in-person visit to the National Archives, or a substantial payment for copying services, which may, or may not, have contained the information sought. Many of those researchers who have previously looked at the dead members of the Stewart family have not revisited them since the advent of wider access to research sources, and this has left the Stewart’s story, and many others, only partially told. Even now, due in large part to the destruction of soldiers’ service records during the 1940 Blitz on London, much of the information needed to tell the story in its entirety is now lost.

What follows here will, hopefully, be a fuller telling of the story of the Stewart family and their experience of loss during the Great War than has previously been told.

The Stewart family was headed by parents James Frederick Stewart and Ada Mears, who married in York in 1882. James Stewart was a musician from Sheffield, and though Ada Mears was born in Stockton on Tees, at the time of her marriage, she was working as a domestic servant in Harrogate, in North Yorkshire alongside her elder sister, Eliza.

Their first child was born in early 1883 in York. The Stewarts called him James Frederick Patrick, and in time, he would follow his father and become a musician, although while his father was a harpist and double bass player, young James became a violinist. Together, father and son advertised their musical services in local press and could attend, with other musicians, all manner of events and functions. It is said that James junior played with Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, and this seems possible, given that he went to live in Liverpool, and in time would enlist into a battalion of the Liverpool Territorials in the city after the outbreak of the Great War.

Charles Edward Stewart was the second child born to the marriage of James and Ada. Like his brother, he too was born in York, in mid-1884. If Charles was musically gifted, he did not pursue it as a career, and by the time he was sixteen, he was working in a warehouse.

A year after the birth of Charles Stewart, William Arthur Stewart (known in the family as Arthur) was born. His birth in early 1886, in Scarborough, shows that the family had moved, but the arrival of the next child, Alfred, into the family in mid-1889 in Great Marlow in Buckinghamshire suggests that the stay in Scarborough was short-lived.

Following a further move, from Buckinghamshire to Leamington Spa in Warwickshire, the only daughter of the family was born, when Ivy Louisa was born in 1890. In 1892 and 1893, two more sons were added to the family, both being born in Leamington. They were Walter and Robert Henry.

Frank Ernest was born in Harrogate in June 1894. He was James and Ada’s eighth child. The family moved to 10 Verdun Street in the Burley area of Leeds shortly after the birth of Frank, but tragedy struck in early 1895 when Frank died, on 16th February, before he reached his first birthday, from convulsions of dentition.

Verdun Street in 1959. The car is parked outside number 10, the Stewart's former home. (Leeds Library & Information Services)

Leonard Stewart was born in Leeds in 1896, and he was followed by Douglas in September 1897. Douglas became the second of the Stewart children to die as an infant when, in 1898, he too died before his first birthday. Douglas died of marasmus, a severe form of malnutrition, at the new family home at 7 Woodsley Grove, Burley. Frank and Douglas were buried in common graves in Leeds General Cemetery, in Woodhouse, which is now incorporated into the precincts of the University of Leeds. The cemetery has largely been cleared of headstones and is used as a green space, although the cemetery chapel still stands.

In the census of 1911, James Stewart states that a third child had died, but all efforts to trace this child have failed. There are few gaps between the births of the known children that are long enough to fit another pregnancy in, and those gaps that are, have been closely examined for suitable names of children who had died before the next census was compiled, with no found match.

As we have seen, James junior became a professional violinist and in his younger days worked with his father, while Charles went to work in a warehouse. Arthur became a draper and tailor’s commercial traveller. Ivy, Walter, and Robert all went into the printing business, with Ivy and Walter being packers, however, Robert underwent an apprenticeship in gold blocking to produce high quality and distinctive designs on stationery.

At the age of twenty, in 1904, Charles Edward Stewart, an accomplished amateur athlete and wrestler, enlisted into the Worcestershire Regiment, and was posted to the regiment’s 1st Battalion, which was serving at Templemore in County Tipperary, Ireland. He served in Ireland for three years before leaving Regular Army service and transferring to the Reserve on 5th August 1907. Back in civil life, Charles Stewart, like his brother, Arthur, became a commercial traveller for a draper and tailor.

Charles’s decision to join the army may have influenced Alfred to do the same, but perhaps wisely, he did not opt to enlist into the regular Army immediately. Instead, he joined the Special Reserve Battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment and reported to the regimental depot at York on 28th November 1908 to undergo the six months of mandatory military training all Special Reservists were obliged to take when they enlisted.

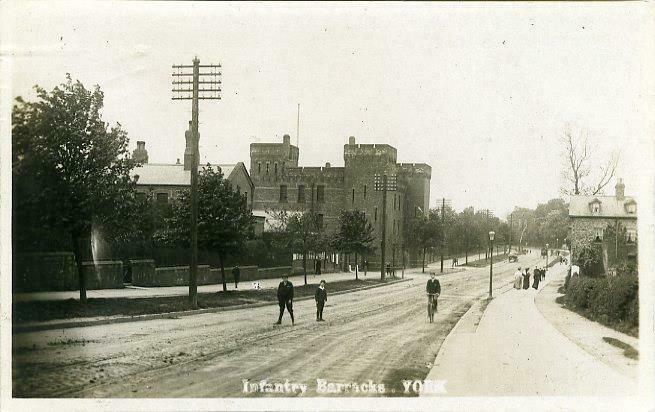

The Infantry Barracks in Fulford, York, the Regimental Depot of the West Yorkshire Regiment

The Army lifestyle and training must have appealed to Alfred Stewart, and instead of remaining as a Special Reserve soldier on the completion of his training, he opted to leave and enlist into the Regular Army. His enlistment into the West Yorkshire Regiment on 14th May 1909 saw him spend another six months at the depot before being posted to the 2nd Battalion of the regiment at Colchester in Essex. In civil life, Alfred Stewart had been employed as a groom, which may have helped him to secure a place for himself as an officer’s servant. After two years serving in Colchester, the battalion was posted out to Malta to take up garrison duties on the island. The sailing to Malta, aboard HMT Rewa took a week, arriving in Malta on 17th January 1912. The battalion remained in Malta until it was recalled at the outbreak of the Great War, leaving on HMT Galicia on 14th September 1914, and going into a transit camp at Baddesley in Hampshire, before transferring to Hursley, near Winchester, to concentrate with the rest of 8th Division which was forming in the vicinity. It is interesting to note that both the Rewa and the Galician (renamed Glenart Castle on transfer to the Union Castle Line) were converted for use as hospital ships during the Great War, and despite both displaying the red cross prominently on a white hull, as well as lighting as hospital ships, both ships were torpedoed in the Bristol Channel within six weeks of each other in January and February 1918.

Alfred Stewart, now appointed a Drummer, sailed with his battalion from Southampton to Le Havre to join the British Expeditionary Force overnight on 4th and 5th November 1914.

Charles Stewart had been recalled to the Colours on the day war was declared and had been serving as a corporal with 2nd Battalion Worcestershire Regiment since 5th August 1915, and his battalion crossed to Boulogne from Southampton with 2nd Division nine days later.

By the end of August 1914, a third Stewart brother was in uniform with the enlistment of Arthur Stewart into the West Riding Regiment. At the time, he was living in Burslem in Staffordshire, where he and his father were members of a local theatre orchestra, but he travelled to Bradford to enlist on 21st August 1914. He joined the 8th Battalion, which was forming at Halifax and would go into training with the remainder of 11th (Northern) Division at Belton Park, near Grantham, the Lincolnshire estate of the Third Earl Brownlow.

Charles was the first of the Stewart brothers to go into action. His battalion was heavily involved in the fighting at Mons and the subsequent retreat to the Marne. Despite having very little time to reacquaint himself with the ways of the army, his conduct during that desperate introduction to war was recognised by his name being mentioned in a despatch from the Commander in Chief of the British Expeditionary Force, Field Marshal Sir John French. The award of a Mention in Despatches was most probably for his part in the action fought by his battalion at Gheluvelt in October 1914.

Worcestershire Regiment and South Wales Borderers at Gheluvelt 31 Oct 1914 (Worcestershire Regiment Museum)

Alfred Stewart, on the other hand, did not have such an illustrious introduction to war fighting after arriving in France. His battalion was involved in the routine holding of trenches in the area near Ploegsteert, close to the border of Belgium and France, but winter was closing in on the fighting lines and the trenches the West Yorkshire men were holding were sodden and knee-deep in mud. Within days, Alfred Stewart was suffering the effects of living outside in such poor conditions, and in mid-November, he was in No 1 Stationary Hospital at Rouen suffering from frostbite. He was evacuated to England aboard HMHS Carisbrooke Castle on 6th December 1914. He was transferred to 3rd (Reserve) Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment, which was based in Whitley Bay.

Alfred Stewart was retained by the 3rd Battalion while he remained unfit for front line service. He was in Whitley Bay until 30th March 1918, when he left to return to France. During his time with the reserve battalion, he met Hannah Woodhouse, and the couple married at St Paul’s Church in Whitley Bay on 19th August 1916. Hannah gave birth to a daughter, Esther Ada on 21st June 1917, registering the birth in Jarrow.

The fourth Stewart brother to join the Army was Leonard, a piano teacher. He joined the West Yorkshire Regiment at the depot in York on 27th February 1915, the day after enlisting in Leeds, and was sent for training to the Reserve Battalion in Whitley Bay, where his brother Alfred was recovering from his frostbite. Serving in the same battalion as his brother may have influenced Leonard in becoming a Drummer, like Alfred was. Leonard’s service records have not survived, so any statement of when he was sent out to France is unavoidably vague. His Medal Index Card shows no entitlement to a 1914-15 Star, and therefore, we can be certain that he did not proceed to France until 1916, some nine months after his enlistment. The usual length of time for a soldier to be in training before being posted out to the BEF was about three months. It is likely that the deployment of Leonard Stewart was delayed due to ill health. Soldiers held in the reserve battalions were reviewed by medical boards on a regular basis, with those deemed fit to deploy, posted off to their appropriate Infantry Base Depot on the French coast for final training before being drafted to a fighting battalion. That Leonard Stewart was not posted to the BEF until at least January 1916 indicates that he did not become fit for quite some time.

The news that Charles Stewart had been Mentioned in Despatches was published in the London Gazette in February 1915, and this was quickly followed by promotion to Sergeant. The 2nd Battalion, Worcestershire Regiment was now near Festubert, in Artois. Neighbouring formations had fought the Battle of Aubers on 9th and 10th May. Two British and one Indian Corps went into action to support and augment the French attack which took place at the same time. The battle was an utter shambles and a disaster for the British and Indian Corps, which lost more than 11000 casualties in the fighting, for no material gains. Their contribution to the battle did nothing to aid their French allies. The Battle of Festubert was almost a continuation of the actions at Aubers, and the British formations were again in support of a much larger French offensive to the south near Vimy Ridge. For the British, the fighting at Festubert was more successful than the Aubers battle, but casualty numbers were still high. The 2nd Division, to which 2nd Worcester belonged had suffered such casualties that it needed to be withdrawn from the line after the fighting was over. Charles Stewart was wounded in both legs in the Battle of Festubert.

Back in England, the 11th (Northern) Division was still in training at Belton Park. The division would sail from Liverpool in July 1915 bound for Suvla Bay on the Gallipoli Peninsula where an expeditionary force had invaded Turkish territory in April. The basic plan had been for a large force to be landed on the peninsula, which would then fight its way to Constantinople, which would be captured, knocking Turkey out of the war, which would allow Russia a maritime exit from the Black Sea through the now safe narrows of the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles.

Soldiers of 11th (Northern) Division leave Belton Park for Liverpool (National Trust)

The plan had failed, and, since landing, the divisions of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force had largely been contained by the Turkish Army in their invasion beachheads. The fighting was desperate and brutal, the weather conditions could be extreme, and the logistical problems of keeping the invasion force supplied and fit to fight were as difficult as they could be. Diseases associated with poor hygiene ran rampant through the soldiers on the peninsula because sanitation without a reasonable supply of water was impossible. This was the environment into which Arthur Stewart and 8th Bn West Riding Regiment landed on 7th August 1915.

The battalion had landed on the Greek island of Lemnos, where it bivouacked for twelve days before leaving for Imbros. The battalion embarked for the peninsula on 6th August, and while the landing at Suvla was uneventful, the battalion was heavily engaged later in the day and suffered heavy losses. The battalion lost its Commanding Officer two days after landing. On 18th October 1915, the battalion went into trenches at Jephson’s Post near the northern end of the line in the Suvla sector. The battalion war diary records that the working parties that the battalion was obliged to send out to maintain and improve their defences were constantly sniped at, with several men killed each day. While those numbers were relatively low, the threat of being shot by a sniper would have made the men dread anything which forced them to be exposed out of their trenches. On 24th October 1915, Arthur Stewart was one of five men of the battalion to be shot by a Turkish sniper. The other men lived, but Private Arthur Stewart was dead. The 8th Battalion West Riding Regiment lost 216 men while it was fighting on Gallipoli. The nature of the campaign dictated that 179 of those men could not be recovered for burial, or could not be identified if recovered, and those men are now commemorated on the Helles Memorial at Seddülbahir at the very bottom of the Gallipoli Peninsula.

The Helles Memorial, Gallipoli (CWGC)

The news of Arthur Stewart’s death was published in the Leeds newspapers on 22nd November. The death would have been devastating to any parents, but the potential of what the war could cost the Stewart family will have brought into sharp focus, as by the end of November, both James and Walter Stewart had volunteered for the Army.

Now, there remained only two sons who were not in the army, and that was only because both had been rejected on health grounds when they had attempted to enlist. Robert Henry Stewart was undaunted by his rejection from the army, and instead, offered his services to a shipping company of the Mercantile Marine, serving from April 1915, as a musician on the SS Transylvania, which was in service as a troopship. The ship was torpedoed in 1917 21/2 miles off the Italian coast, near Savona. After a first torpedo struck, escort ships began taking off survivors, when a second, which was fired at one of the escorts struck the Transylvania. The ship sank immediately with the loss of 402 lives.

George Mears Stewart, the youngest son of the family, was initially rejected on health grounds, but as the war progressed, and the need for men increased, medical standards were reviewed and reduced. By that time, George was ‘engaged in work of National importance’ and had secured a conditional exemption from military service on ‘domestic grounds’, which may have been because four of his brothers had died before the end of the war. When a man was granted a conditional exemption, the conditions imposed on him were usually that he would join and train with his local unit of the Volunteer Training Corps, that he would maintain a good character, and remain employed in the nationally important job that he was doing. Any breach of any of the conditions could see the man brought before magistrates and remanded for military escort.

James Frederick Patrick Stewart, the eldest son of the family, had married Lilian Webster in Leeds in 1906. Their first child, named after his father, was born in the city in 1907, before the family moved to Peterborough, where a second son, George Ernest was born in 1911. At this time, James Stewart was employed as a violinist by the Peterborough Hippodrome, but by 1913, he had been employed by the Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and the family moved to live in Bannerman Street in Edge Hill. The couple added three daughters to the family; Lilian in 1913, and twins, Edith, and Ada in 1914 but, tragically, Edith died aged just 7 months old.

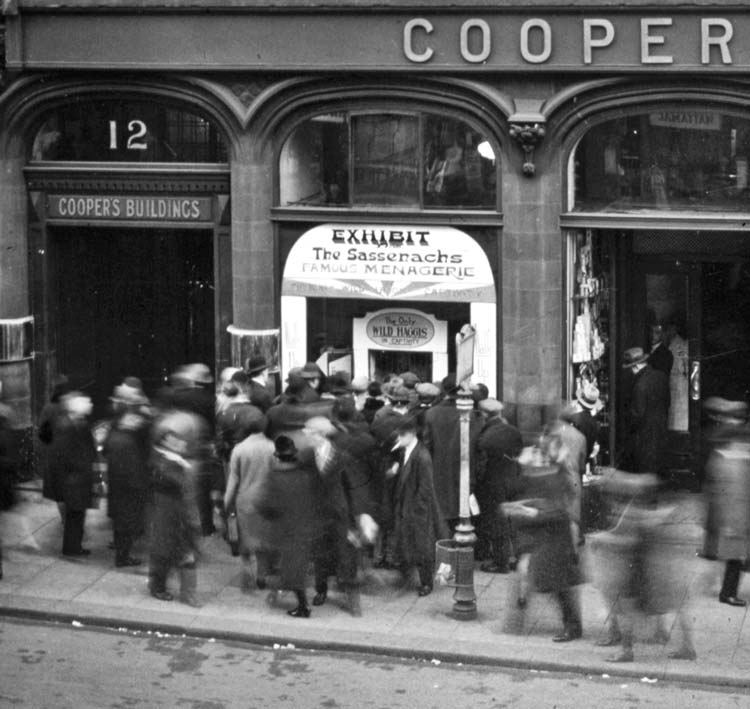

Coopers Buildings, Church Street, Liverpool in the 1930s. The Recruiting Office was in No 12 (Streets of Liverpool)

James Stewart enlisted at the Cooper Buildings in Liverpool on 6th November 1915. He joined 5th Battalion, the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment, and was posted to the 3/5th Battalion which was in training at Weeton Camp, near Blackpool, and shortly before he was sent to France, six months later, the battalion moved to Oswestry.

Walter Stewart enlisted into the Army Service Corps. His records have not survived, but his service number was issued from a batch that was given to men who were employed in civil life as bakers, and who enlisted into the army as bakers in the ASC’s Supply Department, so it appears as though he had switched from working for a printer before he joined the army. He enlisted in Leeds, and joined at Aldershot, reporting to A (Depot) Company at Buller Barracks in the garrison’s South Camp.

Sergeant Charles Stewart’s battalion, 2nd Bn Worcestershire had been transferred into 33rd Division at the end of 1915. The move was designed to bring some experienced battalions into a newly deployed division to be a steadying influence on it. The 33rd Division occupied a sector of the line near Cambrin and Quincy. It was at around this time that Sergeant Charles Stewart left his battalion to train for a commission. Before he left the battalion, his name had been put forward for recognition for an act of personal bravery which resulted in the award of a Military Medal. The award was announced in the London Gazette on 10th October 1916. Most of the other awards that were announced in this gazette were for the first two weeks of the Battle of the Somme, but as Charles Stewart had left for officer training before the battle began, the act for which he was recognised must have occurred earlier than that, but the battalion’s war diary gives no specific clues as to when it may have been.

The day before his brother left 2nd Bn Worcester Regiment, James Stewart was sent to France to join 1/5th Liverpool Regiment. The battalion was holding the line at Wailly, south west of Arras, and although it was not involved in any organised offensive action at the time, the battalion diary records that the German Minenwerfer was frequently fired at the battalion’s trenches, which the battalion scribe described as ‘Our chief cause of anxiety at present. It is extremely damaging to men, material, and moral (sic), and is most difficult to locate’.

Just as the minenwerfer activity lessened, and on 9th July, after only 10 days in France, and probably about a week with the battalion, James Stewart was shot by a sniper. The wound was a ‘Blighty one’, and Rifleman James Stewart was evacuated from France. His journey ended at 3rd Northern General Hospital in Sheffield on 17th July 1916. After a month in the hospital in Sheffield, he was sent home to Liverpool for ten days’ leave, during which time, a transfer to 3/5th Liverpool Regiment at Oswestry was organised.

James Stewart’s service papers and his medal roll entry show a period of attachment to 21st Battalion, Manchester Regiment, beginning on 16th July 1916, the day before he arrived in Sheffield. It may be that he had been selected for temporary attachment to the Manchester Regiment before he was wounded, and an administrative error let that process play out even though he had been wounded. The normal process for dealing with men evacuated to England would be for them to be struck off the strength of their fighting battalion and transferred, in the case of Regular and New Army soldiers, to their reserve, or Depot battalion, or in the case of Territorial Force soldiers (which James Stewart was) to the third line battalion. It would be most unusual for a man to be transferred to a different regiment under this circumstance, which suggests the breakdown of administration.

Charles Edward Stewart (Yorkshire Evening Post 20 September 1916)

After successfully commissioning as a Second Lieutenant, Charles Stewart was transferred to the Manchester Regiment and posted to the 20th Battalion, where he arrived on 30th June 1916. The following day, the battalion took part in the 1916 summer offensive which was to become known as the Battle of the Somme. A joint Anglo-French offensive, the British infantry would attack German positions across a sixteen-mile front which had been subjected to a week-long artillery bombardment which grew in intensity as ‘Zero Hour’ approached. The battalion diary records that 82 other ranks also reached the battalion with 2nd Lt Stewart, and when the main body of the battalion went into the positions it would attack from, this draft of men was left with the transport and reserve elements of the battalion at the Bois de Tailles between Morlancourt and Bray-sur-Somme. It is highly likely that 2nd Lt Stewart was left there too. New men in a battalion, who had not participated in the preparatory training, and did not know the orders for the coming attack would have been a liability in the advance, but their day in battle would come soon enough. Like many other battalions, 20th Bn Manchester Regiment suffered terrible casualties on the first day of the Somme Battle. While the main attack began at 7:30 am, the orders for 20th Bn Manchester Regiment were for the battalion to attack at 2:30 pm. It would attack between the villages of Fricourt and Mametz towards the objective, Sunken Road Trench. German machine guns and grenades inflicted terrible casualties, with 15 of 20 officers killed or wounded, and 310 other ranks out of 670, killed, wounded, or missing. The battalion was forced to withdraw to a support trench and reserve position, which it held until relieved on 5th July. A party of reinforcements joined the battalion on 4th July, when 10 officers (2nd Lt Stewart most probably one of them), and 80 other ranks reported to the acting Commanding Officer.

On 3rd September 1916, 20th Bn Manchester was tasked with attacking the village of Ginchy. Initially the attack went well, with little opposition on the battalion’s front. The battalion to the left of the Manchesters was held up quite early in the attack, and this left the flank of the Manchester battalion exposed, attracting very heavy enfilade fire from ruined buildings in the northern portion of the village, and this fire stopped the advance of the Manchesters as well as inflicting very heavy casualties among the attacking troops. Despite this, the Manchesters managed to get across to the far side of the southern part of the village, but they were forced to retire in the face of a heavy German counterattack.

Second Lieutenant Charles Stewart was wounded by shrapnel during this attack. His evacuation eventually saw him being treated in one of the Base Hospitals at Abbeville, but as his condition was so serious, his family was notified, and his mother, Ada, was able to travel to France to be with her son as he died. Second Lieutenant Charles Edward Stewart is buried in Abbeville Communal Cemetery. To add to the tragedy, Charles Stewart was just weeks away from coming home on leave to get married.

With the death of a second son, and a further four still serving in the Army, the local press in Leeds began to take notice of the Stewarts. At the time of Charles’s death, two sons had died, two were convalescing in England after being wounded or injured, and two, now that Walter Stewart had been sent to East Africa, were on operational service on two different continents.

Towards the end of 1916, James Stewart had recovered from his encounter with the sniper at Wailly. He was declared fit for further front-line service, and on 8th December 1916, he was sent back to France, and re-joined 1/5th Liverpool Regiment.

Leonard Stewart (Yorkshire Evening Post 20 June 1917)

Drummer Leonard Stewart served in the BEF with 2nd Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment. He was seriously wounded near Villers-Guislain during a successful battalion attack on 12th April 1917. The battalion war diary records that one of the companies had been heavily shelled, but suffered no casualties, and later, the men moved off for their own attack against which the Germans put up little resistance. Ably supported by trench mortars, the battalion carried all its objectives, and the battalion suffered just three casualties wounded, Leonard Stewart being one of them.

He was evacuated to England and was admitted to 2nd Western General Hospital in Manchester. It is probable that Leonard Stewart suffered a penetrating wound to the chest which either caused a pulmonary embolism, or became infected, and developed into bacterial pleurisy, causing pain and difficulty in breathing. Bacterial pleurisy, without the availability of antibiotics was untreatable, and patients would be made as comfortable as possible in the hope that their own immune systems would successfully fight the disease. He died in hospital in Manchester on 26th June 1917.

The funeral service for Drummer Stewart took place in the church the family attended, All Hallows, in Burley, although the service had to be conducted by the curate as the incumbent vicar of the church was serving as an army chaplain at the time. Following the service, Leonard Stewart’s remains were taken to Lawnswood Cemetery, in Leeds, for burial in a semi-military committal service involving a bugler and a party of soldiers to fire a volley of shots over the grave. The local press was aware that he was the third of the Stewart’s sons to have died in army service, and at the time of the funeral of Leonard Stewart local newspapers gave brief details about all the sons who were in service or had died. Sympathy was expressed for the parents.

All Hallows Church Burley (Leeds Library & Information Services)

With the opening of 1918, the Stewart family had lost three of their six soldier sons. Remaining on active service were the surviving three sons, and the husband of their daughter Ivy, Pte Albert Scholey, who was serving with 178th Company, Machine Gun Corps. March 1918 brought more bad news for the Stewarts. Their son, Alfred, who had been brought home at the end of 1914 suffering from frostbite, was posted back to France, having been assessed as fit for overseas service. He was promoted Lance Corporal at the same time as he was despatched to ‘E’ Infantry Base Depot at Etaples on the French coast, where he arrived on 30th March 1918.

Three days after his return to France, Alfred Stewart was transferred to the York and Lancaster Regiment and posted to the regiment’s 13th (Barnsley) Battalion. James, meanwhile, was laying in hospital having been wounded for a second time on 13th March. He had received a shrapnel wound in the face during an enemy artillery barrage on trenches the battalion was holding in the Givenchy area. He was not evacuated to England after this wounding but was sent back to one of the base hospitals on the coast of France before being discharged on 25th March 1918 to 10 Convalescent Depot at Ècault, south of Boulogne to recuperate. He remained at Ècault for two months before being found to be fit again, whereupon he was sent to ‘G’ Infantry Base Depot at Etaples, where he stayed for 5 days before being sent up the line to 55th Division Rest Depot Battalion.

Alfred Stewart was killed in action on 13th April 1918. His battalion, 13th York and Lancaster Regiment, had been reformed into a company of a composite battalion following the disaster endured by the British Expeditionary Force during the opening of the German Spring Offensive almost a month earlier. Great swathes of the British lines had been breached by the advancing German army, and many units had lost much of their strength through casualties and men being captured. To effectively put up an opposition to the enemy, many units were formed into composite battalions, but formations such as brigades, which might be expected to be 4000 men strong, were often made up of a quarter of that number. By 13th April 13th Bn York and Lancaster Regiment consisted of six officers and 134 Other Ranks, so despite being described as a company, it was at about half a company’s strength. The composite battalion the 13th York and Lancaster men belonged to was pushed into the line near Meteren to support and strengthen positions held by Australian soldiers.

Ploegsteert Memorial, where Alfred Stewart is commemorated

The position was subjected to a very heavy enemy artillery barrage, during which Alfred Stewart was killed. He has no known grave and is now commemorated on the Ploegsteert Memorial. He was the fourth of the Stewart brothers to die. He was killed only two weeks after returning to France.

James Stewart re-joined his battalion from the Rest Depot Battalion on 4th June 1918. That night his battalion went into the line near Festubert. The trenches were in poor condition and the battalion was obliged to send out large working parties each night to improve the wire defences and generally make the trenches habitable and secure. The Germans appeared content to allow this work to continue without interference from them, provided they knew what was being done, and to find out, they sent aeroplanes out over the British lines to reconnoitre the trenches. What artillery fire the Germans sent over was mainly registering on the roads and tracks behind the trenches, leaving the men in the front lines largely unmolested. That period of relative calm was interrupted on 9th June when the Germans fired a combination of chemical shells into the British lines.

The battalion diary notes that Yellow Cross and Blue Cross shells fell in conjunction with a sneezing gas. The purpose of using a combination of different chemical weapons was to circumvent the protective equipment and immediate action drills the British soldiers were trained to use in response to chemical weapons. Yellow Cross shells contained blister agents, widely referred to as mustard gas. These were viscous liquids which relied on detonation to disperse the liquid in an aerosol form. As it did not readily evaporate, droplets would cling to anything they landed on, and the danger came if a soldier got some on his skin. It could wick through clothes and could penetrate leather, making it difficult to protect against. It was known to remain active in soil for days and weeks after dissemination, meaning it posed a hazard to soldiers crossing contaminated ground long after a bombardment. Blister agents were designed to be incapacitants rather than to kill its victims, based on the premise that a man who was injured would take more men out of a battle as they treated him and evacuated him from the area, while the death of a man only removed him from the battle. They caused horrific injuries which burned and blistered the skin. If a blister was burst, the liquid inside it was a less concentrated solution, but still able to cause further burns and blisters.

I.W.M. Exhibit. Development of the Gas Mask. Portion showing Old Pattern (1916) Box Respirator with Extension Box attached and sections. Introduced early 1917. (IWM Q 65852)

Blue Cross shells contained chemicals designed to irritate the respiratory system. Soldiers could guard against this by using a respirator, which, by 1918 effectively drew the air through filters to neutralise asphyxiants. Therefore, it was delivered in conjunction with a sneezing agent. If a man was affected by sneezing, it might delay his response time in donning his respirator, exposing him to the more harmful asphyxiant agent, or if his sneezing was extreme, he might try to remove his respirator to wipe his face and nose, resulting in more exposure. Excessive sneezing might cause vomiting, which would force a man to remove his respirator.

James Stewart was one of 80 affected by gas on 9th June 1918, including the battalion Medical Officer and three of his orderlies. The following day, he was one of 73 admitted to 22 Casualty Clearing Station at Pernes. He re-joined the battalion from a rest camp on 24th June. He spent much of September 1918 back in the rest camp. He was granted leave in December 1918 but got into trouble by returning a day later than he should have. Finally, in February 1919, he returned to England and was released back to civil life, his wife and family, and his music, from a dispersal camp at the end of the month.

Little remains to inform us about the service of Walter Stewart. The Army Service Corps activities during the Great War were essential to every unit of any size. They moved the food, the ammunition, the stores, the wounded. Their workshop units repaired damaged equipment and vehicles, and their supply units, where Walter Stewart served, amongst other things, ran field bakeries. For a corps of such importance to the operation of an army of more than two million men, at its peak, to have so little written about it is lamentable.

Map showing South Camp, Aldershot, including Buller Barracks, the Depot of the Army Service Corps (National Library of Scotland)

There were at least three ASC Field Bakeries in operation in the East African Campaign, 68th, 72nd, and 73rd. They belonged to the Lines of Communications Troops and were established close to the railways used by the British so that their main product, bread, which is eminently perishable in the climactic conditions there, could be distributed quickly.

Following the end of the Great War the British military presence in East Africa began to be wound down with British soldiers being replaced by African soldiers drawn from the colonies so that the British could be demobilised and returned to their civil lives. Walter Stewart left Mombasa in the then Protectorate of British East Africa, bound for Suez and home aboard SS Marathon, a troopship which had spent much of the war leased to the government of Australia, and operated under the Commonwealth Government Line of Steamers, usually known simply as ‘The Commonwealth Line’. During 1917, Marathon passed back into the operations of the Aberdeen Line, a subsidiary company belonging to the White Star Shipping Line. Walter Stewart died of heart failure on board the ship during the journey home and, in accordance with maritime custom, was buried at sea.

It is unclear what happened, but for many years following his death, Walter Stewart was not recognised as a casualty of war. Work done by the ‘In From the Cold Project’, a group of volunteer researchers dedicated to finding casualties of both world wars who were missing from official casualty records, identified him as qualifying for recognition. Project volunteer Diane Shakespeare built a case and Walter Stewart was accepted as a casualty of war by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in November 2011. He is now commemorated on an Addenda panel on the Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton. The memorial commemorates officers and men of Land and Air Forces who were lost at sea during the Great War.

Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton (CWGC)

The death of Walter Stewart meant that the Stewart family had lost five of their eight sons in military service. Despite the local press seemingly following the plight of the Stewart family during wartime, now it was over, the death of the fifth Stewart son failed to produce any coverage in Leeds newspapers. If it had not been for a notice placed in the family announcements section of the Yorkshire Evening Post on 22nd March 1919, his death would not have been reported at all. Life, it appears, was moving on and the memory of the war was being managed. The casualty lists which had proliferated during the war were gone, and what few men were dying in circumstances like those in which Walter Stewart died appear to be universally ignored. The appetite now was for triumphal parades, lists of local recipients of honours and for war memorials.

The devastation of families like the Stewarts dropped off the pages of the newspapers, and they were largely left to face the future on their own. Of course, the return of sons, James and Robert, and son-in-law, Albert would have brought great joy to them, perhaps heightened due to the losses of the other sons, but the loss was enormous. Alfred left a wife and young daughter to claim his war gratuity, and subsequent pension. When Alfred’s widow, Hannah, married Walter Pomfrey in South Shields at the end of 1919, it ended the widow’s element of her pension, however the element paid for Alfred and Hannah’s daughter, Esther continued until she was 16 years old.

Mrs Ada Stewart received a pension of 14 shillings and sixpence a week for life in respect of Arthur, Leonard, and Walter. She died at her son’s home in 36 Cantsfield Street in December 1934 at the age of 73 years and was buried in Allerton Cemetery in Liverpool on 7th December. She had outlived her husband by 12 years, during which time, her daughter, Ivy Scholey had also died, aged 32 in 1923.

James Stewart, Lilian and two daughters, Vera, born in 1920, and Ada, both tailors, moved to Leeds. During the Second World War, James was a Firewatcher. He died in 1944 and is buried in the family plot in Lawnswood Cemetery. Lilian Stewart died in 1949 and is buried with her husband.

Robert Henry Stewart died in Wakefield at the age of 35 in 1928. He had married Lillian Lowther in Leeds in 1919. He and Lilian, along with two sisters of Lilian’s, Catherine, and Nora, are buried in Killingbeck Roman Catholic Cemetery to the east of Leeds.

George Mears Stewart, the youngest of the brothers had been exempted from service in the Great War, but on the day the United Kingdom entered the Second World War, he was granted an emergency commission as a Lieutenant in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps. He served at the Central Ordnance Depot, Branston, in Burton on Trent, which was the army’s main clothing depot. During this time, he lodged at a boarding house run by the Guy family, on Branston Street in Burton. His commission was converted to a short service commission in 1947, by which time he had been promoted to Captain. George Stewart retired from the army in 1950. He retired to Bournemouth, and died in Poole in 1957, leaving a widow, Mary.

He had married Mary Jane Brown in Leeds in 1922, and the couple had two daughters, Hazel and Sheila.

The Stewarts were a remarkable family, forever changed by war.