The Bombing of the Beaulieu Quarry, 25th September 1917

At its peak during the Great War, the British Expeditionary Force in France and Belgium numbered more than two-and-a-half million men. An army of those proportions required vast amounts of stores to keep the army fed, clothed, and equipped, and to ensure that men, animals, and equipment could be moved to where they were all needed, the army took on responsibility for maintaining and repairing existing road and rail networks, and built many miles of new road and track.

To provide the stone to build roads and the ballast to make track beds, the Royal Engineers created Quarry Companies to serve in France, most of them in cluster of quarries in the Rinxent area of the Pas-de-Calais, roughly 10 miles south west of Calais. The first two Quarry Companies were 198th and 199th, which were formed by the Tunnelling Depot of the Royal Engineers at Clipstone Camp near Mansfield in Nottinghamshire in the summer of 1916. By January 1918, Quarry Companies were established to employ 3420 men in France.

A Quarry Company was commanded by a Captain, supported by 3 Subalterns, either Lieutenant or Second Lieutenant. There was also a Company Sergeant Major, a Company Quartermaster Sergeant and four sergeants. These men formed the military chain of command and would be drawn from fully trained officers, warrant officers and Non-Commissioned Officers of the Royal Engineers, and would be fully equipped as per normal officers and soldiers. There would be eight Corporals, who would act as Foremen directing the quarrying activities of the company, carried out by 244 Sappers, sixteen of whom would be appointed Lance Corporal. These men would be equipped as soldiers, but instead of being issued with rifles, they would be issued with revolvers, although in practice, the arms would be stored in the unit’s armoury unless the man required it for duties. Infantry units would provide a cook and four men to act as officers’ servants.

To provide the stone to build roads and the ballast to make track beds, the Royal Engineers created Quarry Companies to serve in France, most of them in cluster of quarries in the Rinxent area of the Pas-de-Calais, roughly 10 miles south west of Calais. The first two Quarry Companies were 198th and 199th, which were formed by the Tunnelling Depot of the Royal Engineers at Clipstone Camp near Mansfield in Nottinghamshire in the summer of 1916. By January 1918, Quarry Companies were established to employ 3420 men in France.

A Quarry Company was commanded by a Captain, supported by 3 Subalterns, either Lieutenant or Second Lieutenant. There was also a Company Sergeant Major, a Company Quartermaster Sergeant and four sergeants. These men formed the military chain of command and would be drawn from fully trained officers, warrant officers and Non-Commissioned Officers of the Royal Engineers, and would be fully equipped as per normal officers and soldiers. There would be eight Corporals, who would act as Foremen directing the quarrying activities of the company, carried out by 244 Sappers, sixteen of whom would be appointed Lance Corporal. These men would be equipped as soldiers, but instead of being issued with rifles, they would be issued with revolvers, although in practice, the arms would be stored in the unit’s armoury unless the man required it for duties. Infantry units would provide a cook and four men to act as officers’ servants.

Officers of the Royal Engineers and men at the marble quarries at Marquise, 25 November 1918 IWM Q 9708

Of the Sappers, 197 of them would be Quarrymen, most of them directly recruited as skilled men specifically for quarry work, but others were found by way of ‘combing out’ skilled quarrymen who had enlisted into other units and were, therefore, not utilising their skills in a way most beneficial to the army. Also working in the quarry would be twenty static engine drivers, sixteen of them working steam engines, and the remaining four working petrol driven engines to provide power for quarry machinery and electrical power. Two skilled masons completed the establishment of men directly involved in the work within the quarry, but the Quarry Company also employed ancillary trades in a Quarry Maintenance Section which provided support to maintain and repair the machinery in the quarry and in the Company’s office and living accommodation. There were two carpenters and joiners, two gas fitters and plumbers, two platelayers, four blacksmiths, and a tinsmith. Two bootmakers, and a tailor were employed to keep the Sappers’ working clothing and boots, which were exposed to extreme wear and tear, in good order.

A civilian quarryman could expect to earn about 30 shillings per week before the war. A Royal Engineers Quarryman ranked as a Sapper would earn a shilling per day as a soldier, plus a shilling and 2d daily in trade pay, making his army pay only fifteen shillings and 2d per week, a little over half of what he could expect at home, but his food, accommodation, clothing, and equipment were all found at no cost to the man. Those men with dependents at home could claim allowances from the army which often exceeded the pay from his civil employment, which meant that his family would not be financially disadvantaged.

The employer of some of the men who were enlisted into 198th and 199th Quarry Company, the Mountsorrel Granite Company resolved to plan to pay the wives, or dependent widowed mothers of employees who were either Reservists or Territorial force men who had been mobilised ten shillings per week while the men were away and until such time as local relief arrangements could be made. It is not known if this payment was made to the dependents of men who voluntarily enlisted after war was declared, or in respect of those who were conscripted.

The men who would form 198th and 199th Quarry Companies were mobilised in the first week of August 1916 and, after what could only have been the most rudimentary of army training (most the time at Clipstone was taken up carrying out trade testing on the men to assess their declared skills), were sent to France on 24th August 1916. When they began working in the Beaulieu Quarry, the men were organised into shifts to provide labour around the clock and were split to work in the three quarries in the Beaulieu group. Each group on each shift was expected to produce 300 tons of stone ready to be used by the Royal Engineers companies that were tasked with building and repairing roads and railways. The quarries around Beaulieu produced a hard variety of recrystallised calcite, variously but not accurately described as limestone or marble, and would be crushed to provide rail-bed ballast and roadstone.

Despite being in uniform and subject to military discipline, the quarrymen of the Royal Engineers were barely touched by the war. At night, they worked under floodlights, and their accommodation could be lit. The quarries in the Marquise, Rinxent and Beaulieu clusters were far beyond the reach of German artillery, with the front line being roughly fifty miles away, at its closest. Comfortable leisure facilities were provided by the YMCA where the off-duty men could relax with games, writing rooms, libraries, and canteens.

In the late evening of 25th September 1917, work in the Beaulieu Quarry continued as normal, and a new shift had begun work at about 9:10 pm. What had begun as a normal working night for the new shift was, within 20 minutes, transformed into a scene of devastation in the quarry by a bomb being dropped from an enemy aircraft at 9:27 pm. The bomb killed five men and wounded a further six, all of them Sapper Quarrymen, one of whom died from his injuries the following day.

Officers and senior NCOs on the scene immediately took charge of the first aid treatment and rescue of the injured men while sending the uninjured men who were not ordered to help back to their camp. A shortage of stretchers meant that some of the injured had to be carried up from the quarry bottom on doors taken from huts.

A court of enquiry was convened on 26th September, and over two days the board of officers heard evidence from no fewer than eleven witnesses who had held important roles on the night of the bombing raid. The court heard from Sgt Brown, a Royal Fusilier who was attached to the Royal Engineers and would subsequently transfer to the Corps. Sgt Brown told how, as early as 8:00 pm, he had received a telephone call from RE Stores to warn him that firing had been observed in the direction of Calais. Sgt Brown then rang the OC Troops, whereupon the call being answered by OC Troops’ Clerk, Sgt Brown told the clerk what had been seen, and asked for the officer to call him back immediately with a decision as whether the quarry complex lighting should be switched off. Seven minutes later, the officer called back, and after ordering that lights should be extinguished, asked to speak to an officer. Sgt Brown used a buzzer signal to pass the order to put lights out to the quarry powerhouse. Other witnesses confirmed that all the lights in and around the quarry were extinguished at this time.

In the late evening of 25th September 1917, work in the Beaulieu Quarry continued as normal, and a new shift had begun work at about 9:10 pm. What had begun as a normal working night for the new shift was, within 20 minutes, transformed into a scene of devastation in the quarry by a bomb being dropped from an enemy aircraft at 9:27 pm. The bomb killed five men and wounded a further six, all of them Sapper Quarrymen, one of whom died from his injuries the following day.

Officers and senior NCOs on the scene immediately took charge of the first aid treatment and rescue of the injured men while sending the uninjured men who were not ordered to help back to their camp. A shortage of stretchers meant that some of the injured had to be carried up from the quarry bottom on doors taken from huts.

A court of enquiry was convened on 26th September, and over two days the board of officers heard evidence from no fewer than eleven witnesses who had held important roles on the night of the bombing raid. The court heard from Sgt Brown, a Royal Fusilier who was attached to the Royal Engineers and would subsequently transfer to the Corps. Sgt Brown told how, as early as 8:00 pm, he had received a telephone call from RE Stores to warn him that firing had been observed in the direction of Calais. Sgt Brown then rang the OC Troops, whereupon the call being answered by OC Troops’ Clerk, Sgt Brown told the clerk what had been seen, and asked for the officer to call him back immediately with a decision as whether the quarry complex lighting should be switched off. Seven minutes later, the officer called back, and after ordering that lights should be extinguished, asked to speak to an officer. Sgt Brown used a buzzer signal to pass the order to put lights out to the quarry powerhouse. Other witnesses confirmed that all the lights in and around the quarry were extinguished at this time.

The Chief Quarry Officer for the Rinxent area, Major J Phillipson, went up to the Beaulieu Quarry. His evidence does not say why he was at the quarry, but it must be assumed that his attendance was in response to reports of firing further north and reports of an aeroplane engine having been heard. When Maj Phillipson arrived at the quarry he went to the office. He stated the complex lights were not lit when he arrived at 9:00 pm, but soon after he arrived an order came at 9:22 pm from OC Troops for the quarry to switch the lights back on. Maj Phillipson then went with the OC Troops and escorts to view the working are of the quarry. While standing at the west end of the quarry, one of his escorts called ‘Lights out’, and Maj Phillipson said that he immediately heard what he took to be an aeroplane directly above, followed by the sound of four bombs dropping, one of which fell in the quarry. He (and others) initially thought the bomb was a dud as it did not explode until about 3 seconds after it had hit the quarry floor. The force of the blast knocked Maj Phillipson flat on his back, but he was not injured. He estimated that fifteen minutes elapsed before anyone called for stretcher bearers.

With minor discrepancies of perception, the other witnesses called to give evidence to the enquiry agreed on the points of fact of what happened that night which led the panel of officers to conclude that a more effective system was required to pass orders to put the lights out in the quarry in the event of an enemy aircraft being in the area. It recommended that a direct telephone line should be installed between the Headquarters at Rinxent to the powerhouse in the Beaulieu Quarry (and, presumably, the other quarries in the group) so that orders could be passed directly between the HQ and the quarries without relying on an officer to be present to pass the message to. Crucially, it recommended that the powerhouse operator should have the authority to keep lights off until an order came from OC Town Troops in Rinxent, even if an officer in the quarry wanted to turn them back on again.

With minor discrepancies of perception, the other witnesses called to give evidence to the enquiry agreed on the points of fact of what happened that night which led the panel of officers to conclude that a more effective system was required to pass orders to put the lights out in the quarry in the event of an enemy aircraft being in the area. It recommended that a direct telephone line should be installed between the Headquarters at Rinxent to the powerhouse in the Beaulieu Quarry (and, presumably, the other quarries in the group) so that orders could be passed directly between the HQ and the quarries without relying on an officer to be present to pass the message to. Crucially, it recommended that the powerhouse operator should have the authority to keep lights off until an order came from OC Town Troops in Rinxent, even if an officer in the quarry wanted to turn them back on again.

The enquiry further recommended a better system of creating a duty roster for the Duty Officer in the quarry on any shift, as the system in place at the time of the bombing appeared to be nothing better than a verbal handing over of responsibility, and it was felt that because of this, the officer who was thought to be in command of the quarry that night may not have fully appreciated that this was the case, and in the event denied that he was the Duty Officer that night, and no one outside of that quarry had any idea who was on duty, or who was the point of contact in the event of an emergency.

To conclude, the president of the enquiry appreciated that to work at night, the quarry had to be brightly lit and that an aircraft intent on targeting the quarry would be able to see the lights before the troops on the ground would hear the approaching aircraft. He stated that even if the lights were extinguished in good time, the pilot of an aircraft was likely to have a point of reference established in his mind on which he could concentrate until he was directly over the target. In this respect, the president said that making an effective defence against aircraft would be difficult.

Orderly Room Stamp from the Rinxent/Marquise Quarry Group HQ

The men who died on the night of 25th September 1917, and the man who died of his injuries the next day, were taken for burial at Les Baraques Military Cemetery at Sangatte, on the outskirts of Calais and being buried in Rows A and B of Plot I, were among the very first burials in the cemetery.

When we look at the casualties from the quarry that night, we quickly see that all but one of the men killed and injured came from quarrying areas around Leicester. Three of the men were Mountsorrel, and the two dead men from there were known to be former employees of the Mountsorrel Granite Company quarry, with the likelihood that the wounded survivor was as well.

The dead and wounded men were all Group System (Derby Scheme) recruits who enlisted in December 1915 and were then placed on the reserve to await their mobilization orders, which instructed them the report to the Royal Engineers Depot at Clipstone Camp during the first week of August 1916. At Clipstone, the men were organized into 198th and 199th Quarry Companies. They were put through trade tests to assess their skills for grading and pay purposes, and before the end of the month, the men were in France ready to quarry stone.

The men who died were:

196157 Sapper Thomas Westwood, of 198th Quarry Company, Royal Engineers.

Thomas Westwood was born in Dudley in 1877. By the age of fifteen, he was working as a coal mine underground labourer in Cannock. He married May Penny in Ludlow in 1907, and the couple set up home, and began raising a family in the village of Clee Hill, where he worked as a quarryman. Mary Elizabeth was the couple’s first child, born in 1907, and she was followed in 1910 by Doris May. William Percy was born in 1912, with Thomas Roy completing the family in 1917.

Thomas Westwood was born in Dudley in 1877. By the age of fifteen, he was working as a coal mine underground labourer in Cannock. He married May Penny in Ludlow in 1907, and the couple set up home, and began raising a family in the village of Clee Hill, where he worked as a quarryman. Mary Elizabeth was the couple’s first child, born in 1907, and she was followed in 1910 by Doris May. William Percy was born in 1912, with Thomas Roy completing the family in 1917.

On the night of 25th September 1917, Thomas Westwood was seriously wounded, and he died the next day.

196184 Sapper John Henry Pick, of 198th Quarry Company, Royal Engineers.

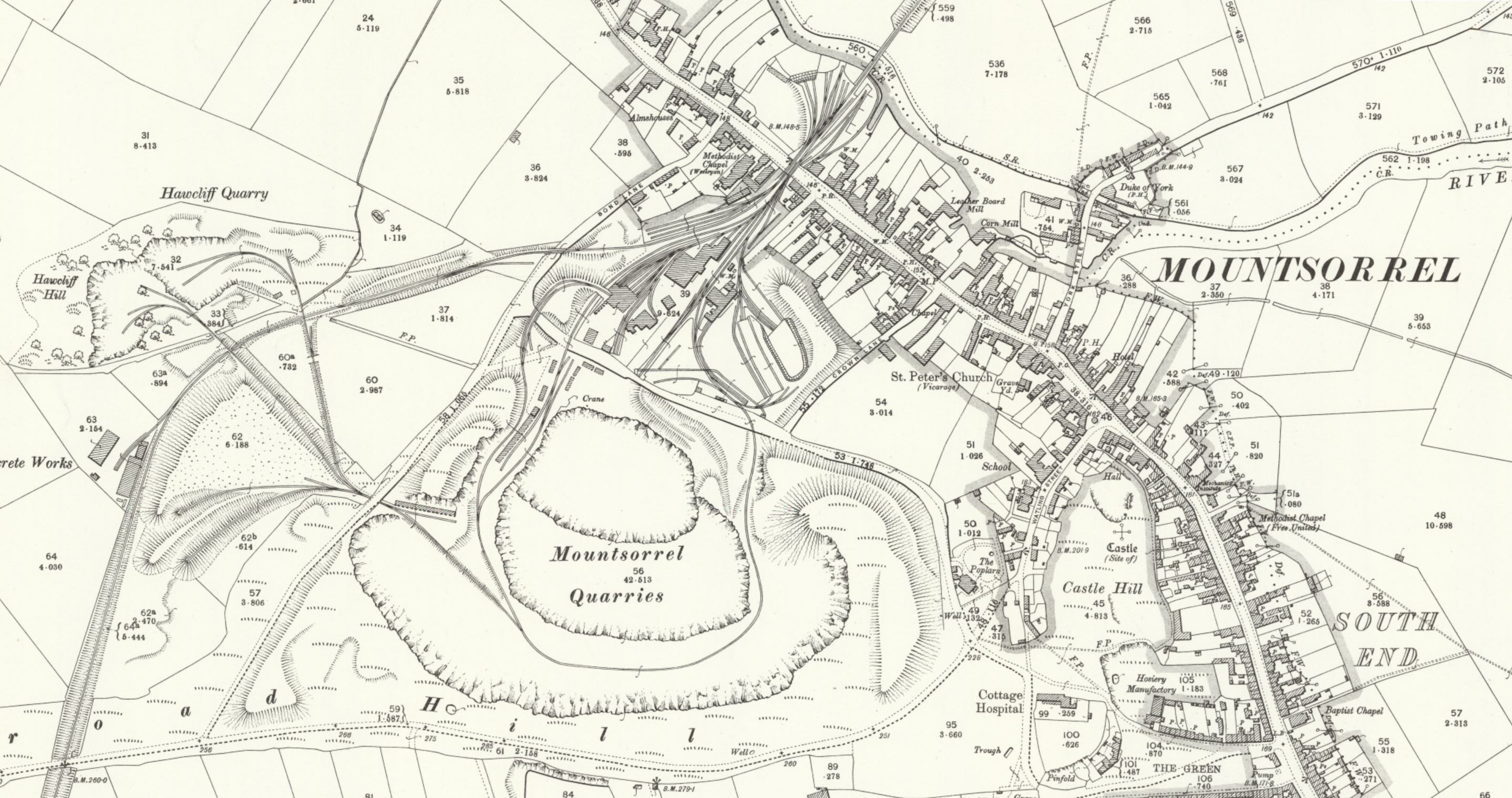

John Pick was one of three Mountsorrel men known to have become a casualty because of the bomb at Beaulieu Quarry. He was the son of George and Emma Pick, of 1 Main Street, Mountsorrel, and the youngest of eight surviving children born to the marriage. Two other children had died in infancy. George Pick was employed as a local corporation road man. His son, John went to work as a labourer at the Mountsorrel Granite Company Quarry.

At the time of his death, John Pick had been married a little over two years. He had married Ada Bagley on 19th September 1915 in the Parish Church at Quorn, a near neighbour of Mountsorrel, separated from it by North End. The three villages sit to the east of the Mountsorrel Quarry works, now operated by the Tarmac Company.

John and Ada Pick did not have any children. In 1923, Ada Pick married Henry Yeomans, and the couple lived in Barrow upon Soar, about a mile away from Quorn.

196206 Sapper Harry Slingsby, of 198th Quarry Company, Royal Engineers.

Harry Slingsby was another of the Mountsorrel Granite Company men to have enlisted into the Royal Engineers as a Quarryman. He was born in Mountsorrel in 1875, and had lived there all his life, going to work in the quarry as a stone dresser after leaving school. He married Ada Dable, also from Mountsorrel, in 1897, and together they had six children; four sons and two daughters, youngest of which, Ada Mary, born in 1916, never saw her father. The eldest son, Arthur, born in 1898, was also a stone dresser, and he too, served as a Quarryman in the Royal Engineers.

196184 Sapper John Henry Pick, of 198th Quarry Company, Royal Engineers.

John Pick was one of three Mountsorrel men known to have become a casualty because of the bomb at Beaulieu Quarry. He was the son of George and Emma Pick, of 1 Main Street, Mountsorrel, and the youngest of eight surviving children born to the marriage. Two other children had died in infancy. George Pick was employed as a local corporation road man. His son, John went to work as a labourer at the Mountsorrel Granite Company Quarry.

At the time of his death, John Pick had been married a little over two years. He had married Ada Bagley on 19th September 1915 in the Parish Church at Quorn, a near neighbour of Mountsorrel, separated from it by North End. The three villages sit to the east of the Mountsorrel Quarry works, now operated by the Tarmac Company.

John and Ada Pick did not have any children. In 1923, Ada Pick married Henry Yeomans, and the couple lived in Barrow upon Soar, about a mile away from Quorn.

196206 Sapper Harry Slingsby, of 198th Quarry Company, Royal Engineers.

Harry Slingsby was another of the Mountsorrel Granite Company men to have enlisted into the Royal Engineers as a Quarryman. He was born in Mountsorrel in 1875, and had lived there all his life, going to work in the quarry as a stone dresser after leaving school. He married Ada Dable, also from Mountsorrel, in 1897, and together they had six children; four sons and two daughters, youngest of which, Ada Mary, born in 1916, never saw her father. The eldest son, Arthur, born in 1898, was also a stone dresser, and he too, served as a Quarryman in the Royal Engineers.

Mountsorrel Quarries Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

196244 Sapper Aubrey James Girdler, of 199th Quarry Company, Royal Engineers.

He was born in Brixton in south London, but 1909, in Croft, south of Leicester, he married local woman, Rose Duncan. Girdler is known to have used Richard as his name instead of Aubrey. It is under this name that he and Rose appear on the 1911 Census, which shows him as a Well Boring Engineer living in Malltraeth on Anglesey. The couple’s first child, Elsie Girdler, was born there in 1912, but by the time they added another child to the family, Aubrey James, born in 1915, the Girdlers had moved back to Croft.

The widowed Rose Girdler remarried in 1923 when she and George Roberts married in Croft. George Roberts was himself a former Sapper of 329th Quarry Company, also from Croft, who had been ‘combed out’ of the Devonshire Regiment to serve as a quarryman. When young Aubrey Girdler left school, he too went into the quarries and became a kerb dresser.

He was born in Brixton in south London, but 1909, in Croft, south of Leicester, he married local woman, Rose Duncan. Girdler is known to have used Richard as his name instead of Aubrey. It is under this name that he and Rose appear on the 1911 Census, which shows him as a Well Boring Engineer living in Malltraeth on Anglesey. The couple’s first child, Elsie Girdler, was born there in 1912, but by the time they added another child to the family, Aubrey James, born in 1915, the Girdlers had moved back to Croft.

The widowed Rose Girdler remarried in 1923 when she and George Roberts married in Croft. George Roberts was himself a former Sapper of 329th Quarry Company, also from Croft, who had been ‘combed out’ of the Devonshire Regiment to serve as a quarryman. When young Aubrey Girdler left school, he too went into the quarries and became a kerb dresser.

196247 Sapper Frank Taylor, of 198th Quarry Company, Royal Engineers.

Frank Taylor came from Stoney Stanton, a village to the south west of Leicester, near Hinckley. He was a sett maker turning out cobbles for road surfaces. At the time of his enlistment, he and his wife, Ellen, known as Nellie, whom he had married in 1909, were living in Huncote, close to the Croft Quarry. A son, named Frank was born in 1911, followed by Annie Elizabeth in 1914. Frank Taylor was aged 29 when he died.

196252 Sapper William Thomas Tite, of 198th Quarry Company, Royal Engineers.

William Tite was born in Frolesworth in 1887. Before joining the army, he was employed as a waggoner. He married Ethel Elizabeth Cockerill in early 1914, and together they had a son, Charles Henry, born in February 1916. The couple lived at Soar Mill Lane, Sutton in the Elms, and after she became a widow, Ethel continued to live there with her children and granddaughter, Elaine. Ethel did not remarry and died aged 69 in 1960.

Frank Taylor came from Stoney Stanton, a village to the south west of Leicester, near Hinckley. He was a sett maker turning out cobbles for road surfaces. At the time of his enlistment, he and his wife, Ellen, known as Nellie, whom he had married in 1909, were living in Huncote, close to the Croft Quarry. A son, named Frank was born in 1911, followed by Annie Elizabeth in 1914. Frank Taylor was aged 29 when he died.

196252 Sapper William Thomas Tite, of 198th Quarry Company, Royal Engineers.

William Tite was born in Frolesworth in 1887. Before joining the army, he was employed as a waggoner. He married Ethel Elizabeth Cockerill in early 1914, and together they had a son, Charles Henry, born in February 1916. The couple lived at Soar Mill Lane, Sutton in the Elms, and after she became a widow, Ethel continued to live there with her children and granddaughter, Elaine. Ethel did not remarry and died aged 69 in 1960.

The wounded men were:

196174 Sapper Alfred Knight, from Huncote.

196195 Sapper Jesse Peters, from Mountsorrel. He was the third Mountsorrel Granite Company employee involved in the bombing at Beaulieu Quarry on 25th September 1917.

196200 Sapper Horace Stevens, from Rotherby. Horace Stevens did not recover from his wounds sufficiently well enough to soldier on, and on 11th November 1918 he was discharged from the army because of them. He was awarded a Silver War Badge on discharge.

196215 Sapper George Harry Pears, from Huncote and,

196225 Sapper Ebenezer Brown, from Stoney Stanton.

Mountsorrel Quarrymen in France 1917 (Mountsorrel Archive - Noel Wakeling)

Sources:

National Library of Scotland - Map Images (nls.uk)

Chris Baker's Long Long Trail

Mountsorrel Heritage Group

Free BMD

Ancestry

Find My Past

The Genealogist

The Great War Forum

Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War 1914 - 1920 (War Office HMSO London, 1922)

National Library of Scotland - Map Images (nls.uk)

Chris Baker's Long Long Trail

Mountsorrel Heritage Group

Free BMD

Ancestry

Find My Past

The Genealogist

The Great War Forum

Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War 1914 - 1920 (War Office HMSO London, 1922)