The Barnbow Explosion - December 1916, and its devastation of a Leeds Family

By the end of 1914, the war in Europe had largely stagnated, because none of the vast armies fighting on the Western Front could deliver the decisive blow to knock the other out of the war and claim victory. A factor in this inability to end the war quickly, at least from the British perspective, was the inability to produce artillery shells in the quantities, and of the quality required for the British artillery to dominate the battlefield.

Until the Great War, the production of artillery shells for use by the army had been almost exclusively the preserve of the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich, which occupied a vast site on the south bank of the River Thames in east London. In peace time and in previous wars, the operations at Woolwich could supply enough ammunition of all kinds to maintain adequate supplies for the Army’s use, but the scale of the Great War, and the reliance of the army on the artillery capability that it had when the war of movement ended and the opposing armies settled down into lines facing each other across a no man’s land meant that demand for ammunition soon outstripped the production capabilities of the Royal Arsenal. A crisis of supply began to severely restrict how the British could operate. Artillery units saw their ammunition allocations rationed to the point of impotence. Often a battery might only be given enough ammunition to allow them to register their guns. A daily allocation of shells might be in single figures per gun.

The causes for the shell crisis were many, but the inability of a single main site to produce the necessary volume of ammunition was clearly one of the major factors. Parliament passed the Munitions of War Act on 2nd July 1915 to address the problems, and to support David Lloyd George who had been installed as the first Minister of Munitions two months earlier. One solution to the supply problem was to create National Filling Factories across the country, which would take in manufactured shell casings and fill them with explosives and fit the fuses before they were transported to storage depots, from where they would be issued to the army.

The Shell Crisis Breaks in the British Press (The Times, 14th May 1915)

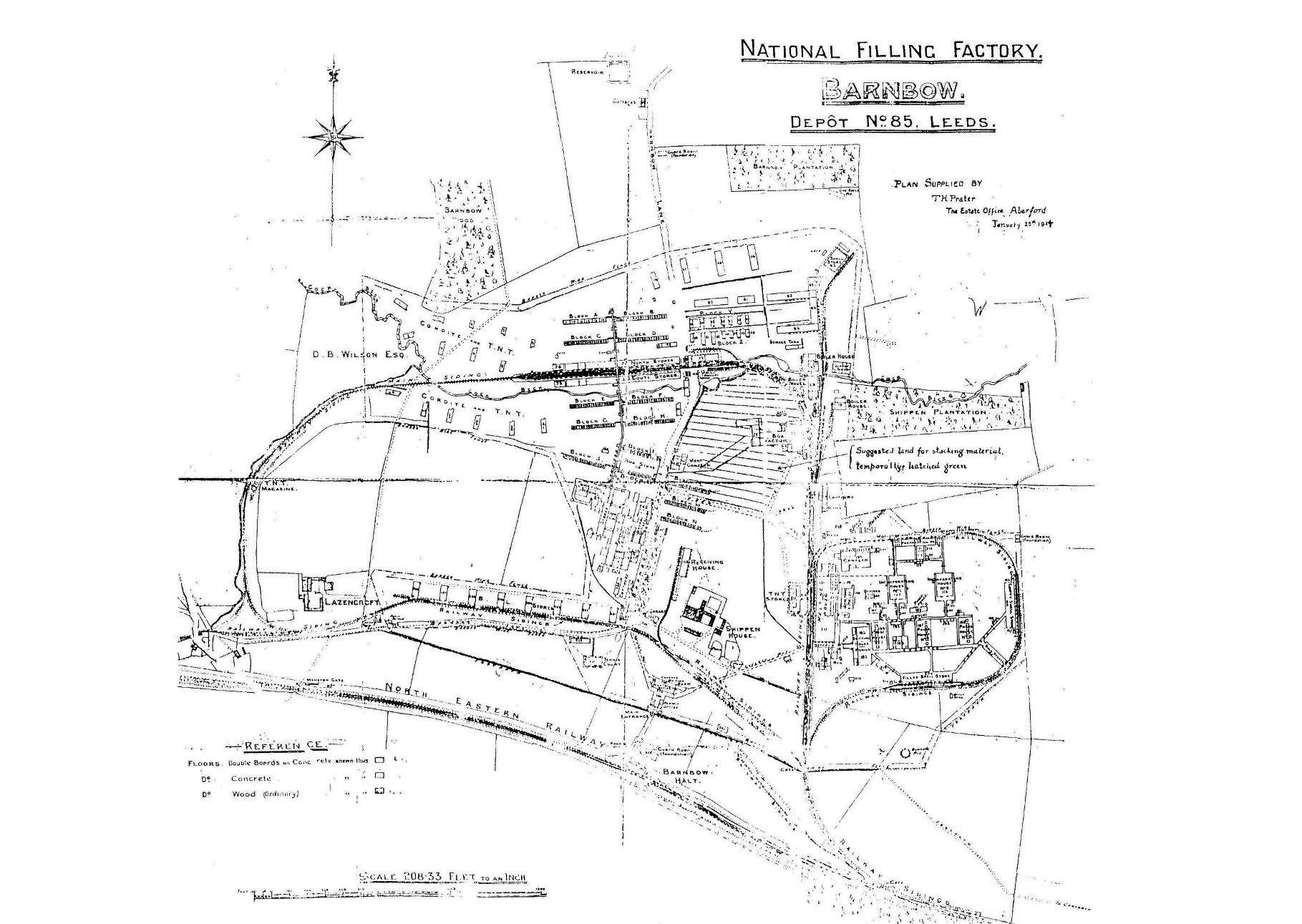

A site at Barnbow, a mile from Cross Gates, and six miles east from the centre of Leeds was chosen for the erection of a filling factory on land rented from local landowner, Colonel Gascoigne DSO of Parlington and Lotherton, with construction beginning in August 1915. At its largest, the site covered some 400 acres, and employed more than 16000 people, with more than 90% of the workforce being women. The site deliberately incorporated the pre-existing Shippen House dairy farm, which grew to keep a herd of 120 milking cows, tended by six women and overseen by a qualified farm bailiff. The milk yield was 300 gallons per day, and this would be issued, in almost unlimited quantities to the women who worked in the filling rooms in an effort to flush out the toxins the women ingested during their work that turned their skin yellow, earning them the nickname ‘Canaries’.

At the time of its construction, the Barnbow site was not easily accessible to anyone coming from outside the immediate area. The Leeds to Selby line of the North Eastern Railway ran past the southern side of the site, but the nearest station was in Cross Gates, a mile away. Very quickly, a dedicated railway halt was built, and up to 38 special trains per day brought the workforce to the site from as far away as York and Knaresborough to keep the three-shift system operating twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

Three canteens catered for the workers, with one able to seat 4000 workers over two forty-five minute sittings, while a special canteen fed the workers in the Amatol sheds with capacity for 1000 workers. The food they served was fresh, nutritious, and plentiful, all of it cooked on site using modern, sometimes specially constructed appliances. Food waste from the kitchens was used to feed pigs reared on Shippen House Farm, which were then slaughtered and butchered on site to supply the kitchens, while spare parcels of land around the site could provide 200 tons of potatoes per cropping season. With malnutrition being a ubiquitous condition of working-class life in an industrial city, the good, affordable meals that were available to those at Barnbow proved to be a persuasive tool to recruit a huge workforce. The workers could also take advantage of dedicated medical and dental facilities made up of a resident doctor, two dentists, and a team of qualified nurses who supervised up to thirty ladies of the Voluntary Aid Detachment. For many of the workers, it would be the first time in their lives that they would have access to good quality medical care.

Part of the Barnbow Complex under Construction (Leeds Library & Information Services)

Wages were good. A worker on munitions production could earn £3/0/0 for a six-day (forty-eight hours) working week, with an increment paid to those working in the ‘Danger Rooms’. Elsewhere on the site, those workers not directly employed on munitions production were paid a little less, but their wages would still be higher than those paid for a comparable job in general industry, but as most of the workers were women, who were largely confined to employment in domestic service or shop work, the uplift in pay that they got from munitions work was considerable.

The work done at Barnbow was undeniably dangerous. Explosive compounds were heated and mixed to produce fillings for shells which had extraordinary explosive power, and the procedures that were put in place to prevent accidental detonations were many and thorough. To ensure that those procedures of changing clothes when entering and leaving the work area and emptying of pockets of contraband items to be left in a personal locker were rigorously followed, the time taken to properly follow them was factored into a worker’s shift, and crucially, it was paid. Routine and irregular searches were made, and those workers found to have matches, cigarettes, jewellery, or even hair pins about their person, could expect to find themselves in front of specially convened magistrates courts to face a fine. The vigilance of the search teams paid off and accidents at Barnbow were rare, but when they did occur, the result was disastrous.

During the three years that Barnbow was producing munitions, there were three explosions at the site, all of which resulted in the deaths of workers. An explosion on 21st March 1917, killed two women workers, while another on 31st March 1918, killed three men. The most devastating explosion occurred on 5th December 1916 in Room 42, a fusing room, and on that night thirty-five women were killed.

Because of the nature of the work done at Barnbow, for the duration of its time as a munitions factory, a news blackout was maintained under the provisions of the Defence of the Realm Act. It was impossible to keep a 400-acre site a secret. Anyone travelling by train to Selby from Leeds could not help but see it as they left Cross Gates, but what went on inside its perimeter fences was not revealed to the public in the press until December 1918, when the first mention of the fatal explosions was printed in local newspapers. The information was fragmentary, and it would be another five years before a detailed account was pieced together, after the site was finally closed in 1924. Since the war it had been used by the Central Stores Department of the Ministry of Munitions to store everything from blankets to railway locomotives and rolling stock.

Plan of No. 1 Shell Filling Factory, Barnbow

An inquest into the deaths caused by the explosion heard that the night shift had begun as normal at 10:00 pm, although, due to a late arriving train, Edith Barratt the chargehand for the room did not arrive at her workstation until twenty minutes after the shift had started. Of the four machines used to screw the fuses into the 4.5-inch Howitzer shells, one was out of order, and another was stiff to operate. Miss Barratt told everyone not to use the machine until it had been repaired by a fitter. A third machine was not screwing the fuses in sufficiently tightly enough, which meant that all the shells that had been finished on this machine were rejected. Miss Barratt also gave instructions for this machine not to be used.

At 10:27 pm, the room was blown apart by a single explosion. The wooden shed was completely destroyed, and those in the immediate vicinity were badly damaged. The hot water heating pipes were ruptured and the hot water spraying into the cold winter night created a steam cloud like a smoke screen. Twenty-three women lay dead in the ruined remains of the shed, some of them so badly injured that they were only identifiable by their identity tags. Another twelve women would die of their injuries in the coming days. Dozens more were wounded and burned to varying degrees.

For the next hour-and-a-half, a rescue operation, carefully rehearsed over the year the factory had been in production, moved in to bring out the dead and injured in conjunction with the factory fire brigade. No-one knew if there would be another explosion.

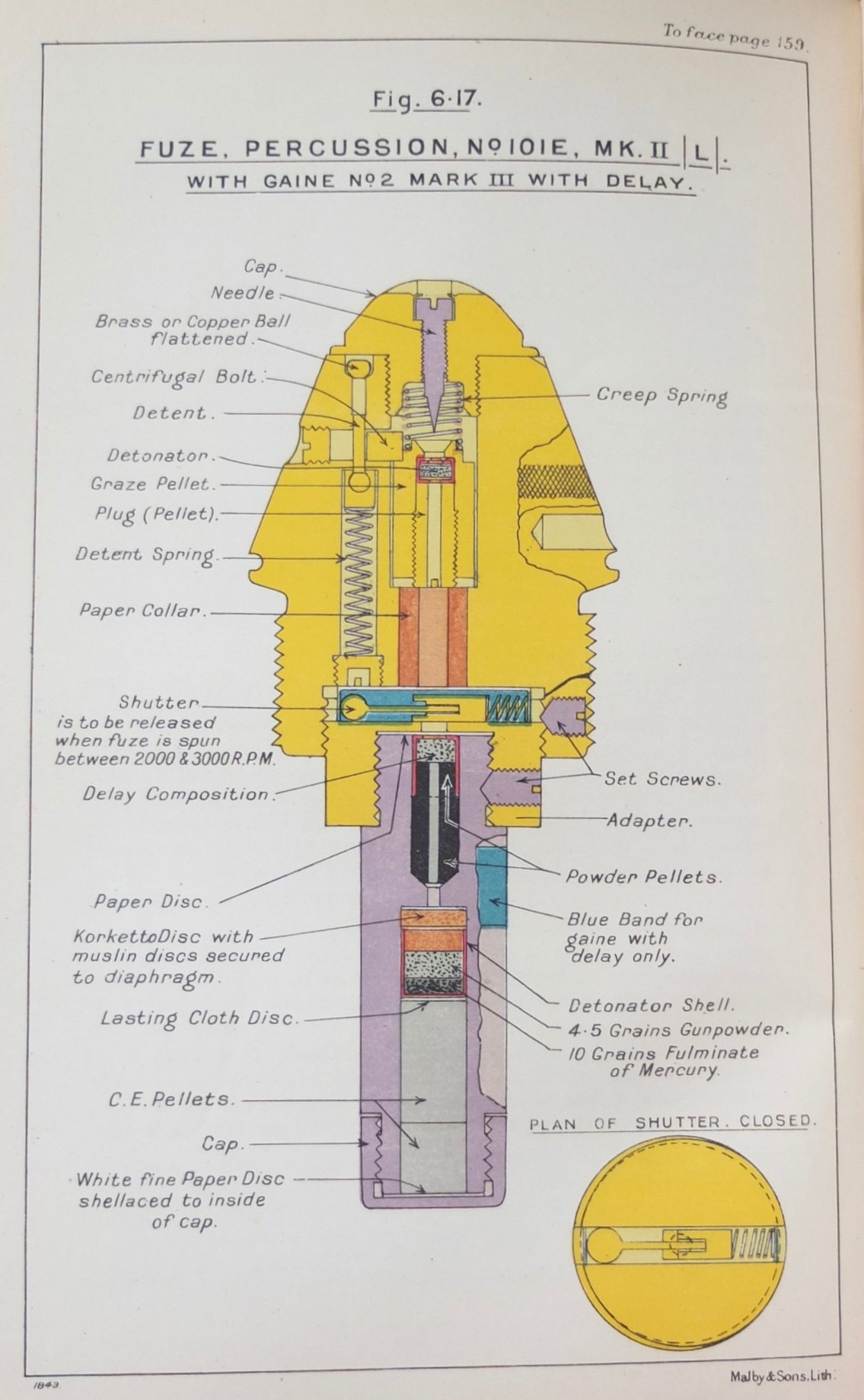

An enquiry into the cause of the explosion examined the remains

of the fusing machines and quickly ruled them out from being to blame. Colonel

Sir Hilaro Barlow from the Ministry of Munitions came from London to

investigate, but much of the evidence he wished to examine had been destroyed

in the explosion. The report he submitted suggested that the explosion was

triggered by a faulty gaine*, which had probably become separated from a fuse and been left in the cavity of the explosive charge which had then detonated as another fuse was

attached to the shell, but he did stress that he could not be sure without the

evidence he needed. The jury accepted the colonel’s suggestion.

* A gaine was a separate enclosed charge, fixed to the fuse, used to create a flash which initiated the detonation of the main explosive charge.

The Fuse used in a 4.5-inch Howitzer HE Projectile (Textbook of Ammunition - HMSO 1926)

Although, at the time, there was no official reporting of the December 1916 explosion, the news of it spread to the outlying towns and villages that were the homes of the workers at Barnbow. The hospitals of Leeds had received the injured, and the medical staff at each one will have known the scale of what had happened that night. One such doctor was working at East Leeds War Hospital, caring for the desperately ill William Bainbridge, a forty-one-year-old, discharged Leeds Rifleman who was suffering from advanced tuberculosis. The instant the news that his wife, Kate Bainbridge, had been killed during the night was broken to him, William Bainbridge’s world collapsed.

William and Kate Bainbridge were an unmarried couple who lived at 38 Ward’s Fold in the Mabgate area of Leeds. This, and the neighbouring Leylands, were among the most deprived areas of the city, where poor quality, densely packed housing existed cheek by jowl with workshops and factories of all descriptions. The people who lived, or rather, existed, in these areas, did so in a state of perpetual, grinding poverty, on wages that frequently fell short of what their landlords charged for rent. They struggled to put food on their tables and often relied upon charity to clothe themselves and their children. Many were driven to crime or prostitution in their desperation to push their eviction back by a week or two. There is no suggestion, and no evidence to suggest that William Bainbridge, or his unmarried wife, Kate Yates, as she was properly known, were drawn into either, but having no place to go other than Mabgate is evidence enough of how hard their lives were, and with four children to provide for, there would have been many times when their money ran out before the next pay day.

When William Bainbridge volunteered for the army on 21st June 1915, at his age, and already in poor health, the likelihood is that he did so for financial reasons. The army would pay the soldier a regular wage, while clothing, feeding, and housing him on an ‘all found’ basis. In other words, he would not have to pay any extra for any of those things. Married men could claim a separation allowance to help their wives keep up with the costs of running a house, and an increment would be allowable for each child under 16 years of age in the household. In many cases, especially for the inhabitants of areas like Mabgate, the allowances paid by the army would be more generous than their income from civil employment. Many unmarried couples did get married to qualify for these allowances, but there is no record of William Bainbridge and Kate Yates marrying. While it is possible that she had already been using Bainbridge as her surname when William joined the army, she was certainly using it after he joined. The money received in allowances from the army would have gone a very long way towards making the home life of the family at least secure, if not comfortable.

Tunstall's Fold in the Mabgate area of Leeds. Conditions in Ward's Fold were the same. (Leeds Civic Trust)

Kate Yates’ life since she was a child had been punctuated with spells as an inmate in the Leeds Union Workhouse on Beckett Street in the city. She was an inmate at the time of the 1901 census, and in 1911, when the next census was taken, she was, with her new daughter, Doris, a patient at the Leeds Union Infirmary which was attached to the workhouse. A person didn’t have to be an inmate of the workhouse to be admitted to the infirmary, but those who were admitted had to demonstrate that they were unable to pay for treatment from any other provider.

Separately, and together, the pre-war lives of William Bainbridge and Kate Yates, and those of the children had been hard. They existed in chronic, unrelenting poverty with only a string of cramped and unsanitary housing available to them. Four of Kate Yates’s children died before their second birthday. For the Bainbridge family, the war finally brought the opportunity to earn a regular and adequate income. For Kate Bainbridge, the transformation from being dependant on the workhouse and the Union Infirmary, to being able to earn £3/0/0 per week working at Barnbow would have been unimaginable. Even when she was able to get work as a charwoman, she would normally earn only a quarter of the money she earned making munitions. She was 40 years old when she was killed and was buried in a grave at Killingbeck Roman Catholic Cemetery that remained unmarked for decades.

A medical report on William Bainbridge, made on 6th December 1916 at East Leeds War Hospital, the morning after the explosion makes particularly tragic reading. He had been discharged from the army, without any overseas service, on 26th October 1915, after a little over four months’ service, because of his tuberculosis. He was unable to find work afterwards, and had received a £1/0/0 gratuity, with 4s/8d per week as a pension from the army, with a further 8 shillings in respect of the children. On 1st December 1915, he attempted to enlist again, but because of his current bronchitis and signs of tuberculosis, he was rejected, with the doctor noting that ‘For the purposes of the services, he is useless’. After his rejection from the army, William Bainbridge was able to find employment at the National Shell Factory on Goodman Street in Hunslet, however the heavy labouring job was beyond his capability with his health deteriorating rapidly.

The doctor who wrote the medical report on 6th December said, ‘Very hard case. Wife killed last night at Barnbow explosion, and he has 4 children – oldest 9. He is extremely ill and urgently needs money.’

Ironically, The Leeds Union Workhouse, and its Infirmary, where Kate Yates had been an inmate, had been offered, by the Leeds Board of Guardians, to the War Office and became East Leeds War Hospital soon after the war began, and it was here that her husband was laying, grievously ill.

It appears that when William Bainbridge took employment at the National Shell Factory, he forfeited the on-going element of his pension, and as he was now unable to work, he had no income. A new pension application was made on his behalf in October 1916, but this was rejected a month later after the commanding officer of 7th (Reserve) Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment refused to support the application. He wrote ‘Man was not subjected to any exceptional hardship, etc. Whilst with his battalion, he was in barracks and had 2 suits and 2 pairs of boots.’ This rather unsympathetic assessment of William Bainbridge’s circumstances completely ignored the fact that those listed benefits, the barracks and his uniform, would be lost to him on his discharge from the army.

The Medical Report which almost guaranteed that William Bainbridge would be left penniless. (WO 364/113)

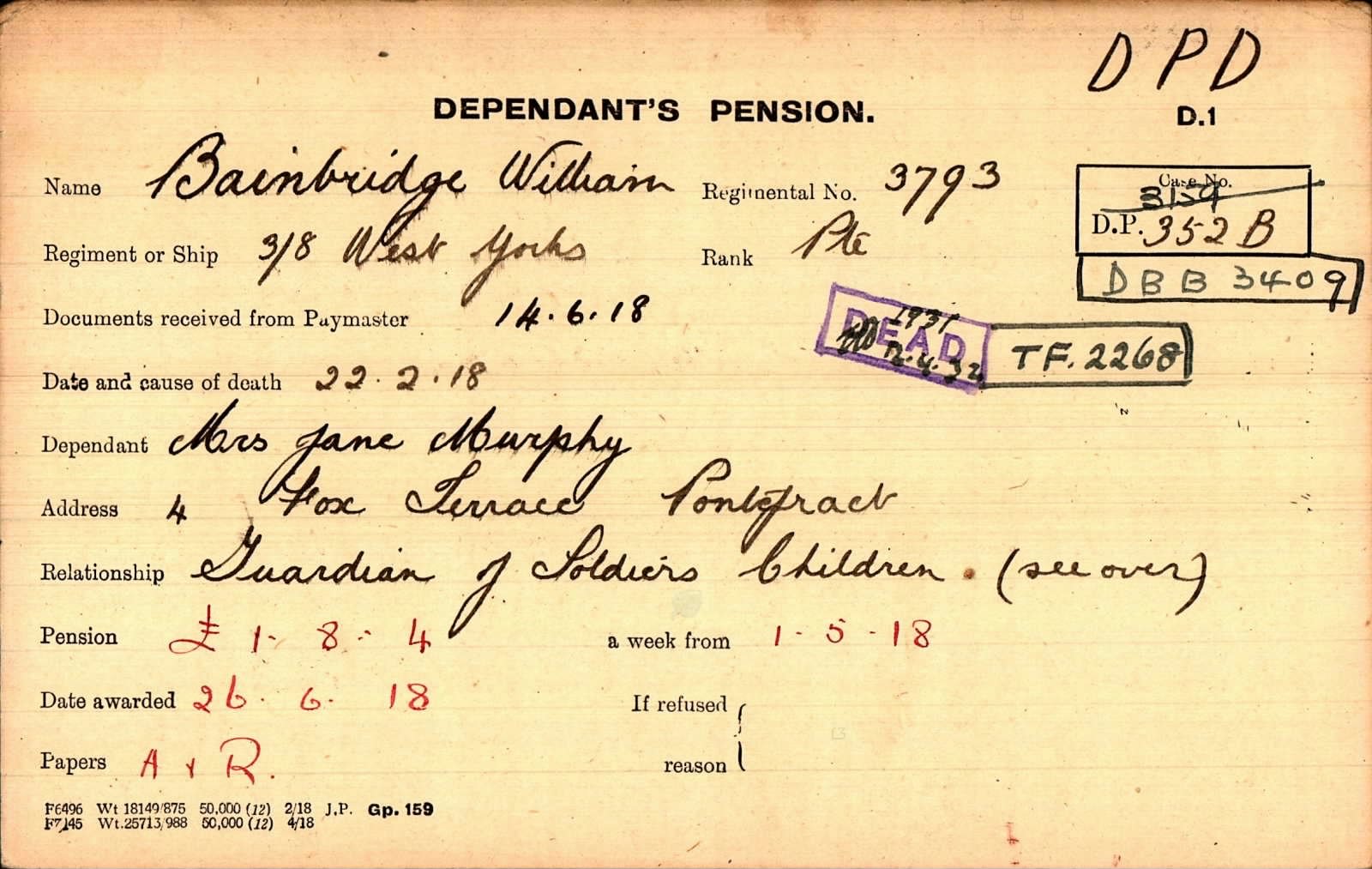

Following the death of Kate, William Bainbridge, without any form of income, was unable to cope with four young children by himself. Although his father was still alive, he was destitute and homeless in the care of the Church Army in Kirkgate, Leeds, and unable to help his son. Fortunately, William had a married sister, Jane Murphy, who lived in Pontefract and ran the Dolphin Lodging House on Horsefair with her husband William, and he was able to move his family there.

William Bainbridge’s tuberculosis continued to worsen, and though he received periods of treatment at a sanatorium, he died in Pontefract on 27th February 1918. He was buried in Pontefract Cemetery, where his grave is marked by a standard CWGC Portland Lime headstone.

With the death of both their parents, the four young Bainbridge children were placed in the guardianship of William Bainbridge’s father, also William. He had been able to leave the Church Army hostel and moved to Pontefract to live with his daughter, however, as he was also in ill health, and getting quite elderly, he relinquished the guardianship to his daughter. The elder William Bainbridge died in 1927.

Dependant's Pension Card showing Jane Murphy as the Guardian of the Bainbridge Children (Western Front Association)

When Jane Murphy died in 1935, William Murphy moved in with William and Kate Bainbridge’s second surviving child, daughter Doris and her husband, Charles Smith. Doris’s brother Albert, the youngest of William and Kate Bainbridge’s children also lived in the Smith household in Fox Terrace.

The explosion at Barnbow in December 1916 affected a small part of the production at the complex. Lines were duplicated so that if production on one was interrupted for any reason, it would continue along the line that was still functioning. While Barnbow was the first and most productive shell filling factory in the country, it was only one of many, meaning that any irregularity in its rate of production was further mitigated by the number of factories across the country which did the same work. Throughout its time in production, the Barnbow Shell Filling Factory despatched 566000 tons of finished munitions for use in the war. For the Bainbridge family, however, the explosion changed everything, forever.

Part of Barnbow No. 1. (Leeds) National Filling Factory after it had been ripped apart by an explosion on the 31st May 1918. This image is used to illustrate to power of the explosions on the site. (Leeds Library & Information Service)

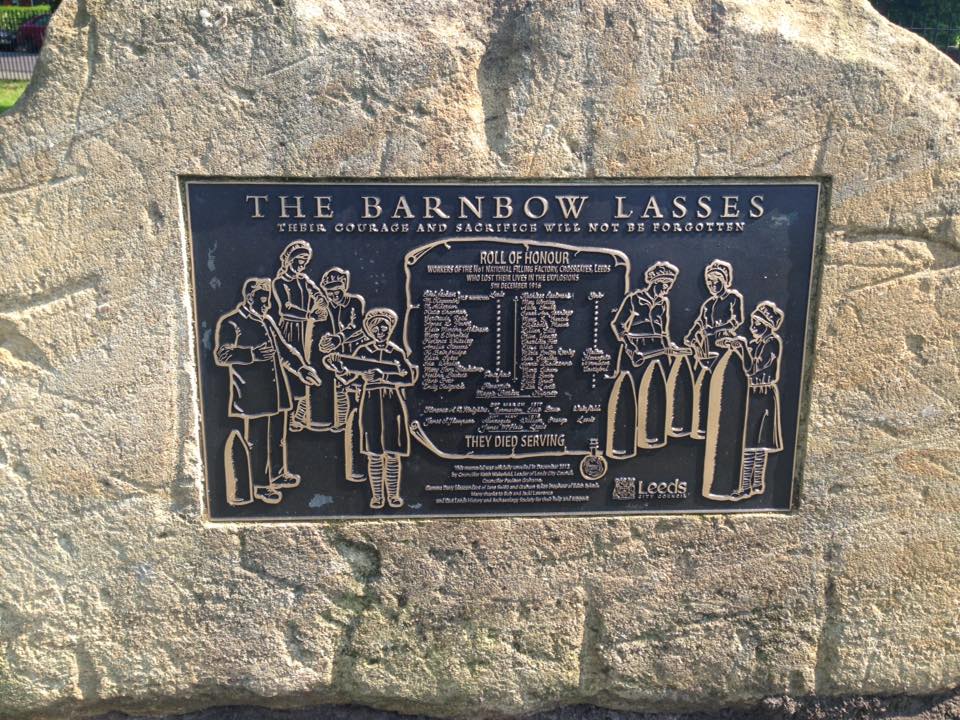

Despite the women who were killed receiving no official recognition for their work, and their graves not qualifying for war graves status, they are collectively remembered by the dedication of the Five Sisters Window in York Minster to ‘The Memory of the Women of the Empire who gave their lives in the European War of 1914 – 1918’, and in the oak panels of the Women’s National Memorial Screen in St Nicholas’s Chapel in the Minster. Individually, the women are named on war memorials in the places where they came from. Four of the women are buried together in the City Cemetery at York.

More recently, Cross Gates has erected two memorials to remember those killed in the explosions at Barnbow. The first was at the top end of Cross Gates Road, consisting of three raised plinths with engraved brass tiles set into the pavement, however, this memorial deteriorated after only a few years. It was replaced by a new memorial in Manston Park, which is made up of a cast brass plaque bearing the names of those killed set on a rough-hewn stone base with a surrounding flower garden.

The Memorial in Manston Park to Remember 'The Barnbow Lasses'

In 1939, the government bought a 60-acre plot of land on Manston Lane, a mile from the original Barnbow factory and constructed a Royal Ordnance Factory on it. Production of tanks began there in 1940 and continued until the completion of the Challenger II order in 1999 by Vickers Defence Systems. The site of the Royal Ordnance Factory has been partially redeveloped with houses being built at the western end of the enclosure. The new roads in this estate are each named in honour of one of the women who was killed in the 1916 explosion, and more are planned. The new East Leeds Orbital Road, which cuts across a small portion of the southern part of the original Barnbow site has a section, including a bridge, named in honour of William Parkin, a manager at the Shell Filling Factory in December 1916, who was one of the first people to enter the destroyed shed and continued to rescue the injured women there until he was sure that the last live casualty had been recovered.

Although there has been much development close to the site of the original factory, the area where the main part of the production took place has largely remained untouched since the site was vacated and the buildings were dismantled and sold. Half of the site has not been returned to agriculture due to the level of contamination that was left in the ground where the mixing sheds were. None of the temporary structures remain, however, a small number of brick-built utility buildings still exist to provide shelter for the sheep belonging to Shippen House Farm. The earthworks which surrounded the filling sheds can still be found.

The entire production side of the site is accessible to the public and may be

walked freely. The eastern side of the complex that was used for fusing and storage

is now working farmland, is private, and should not be entered. It may, however, be easily viewed from Barnbow Lane.

The Scene of the Room 42 Explosion as it appears today.