Submitting a Case of Non-Commemoration to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Often, when engaged in research for a client, items of information, or documents relating to other soldiers will present themselves which cry out for further research in their own right.

Inquest Report into the death of Fred Patrick (Yorkshire Evening Post - 31st March 1919)

One such is the story of Fred Patrick, a Territorial Force soldier from Leeds who initially enlisted into 7th (Leeds Rifles) Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment in 1909. Patrick was a conscientious part-time soldier who attended each of the annual camps that his battalion went on before the outbreak of the Great War and was proficient in his training. When war broke out, he had been promoted to Corporal, and would go on to become a Sergeant days before his battalion was sent to France, which is clearly a mark of the confidence his officers had in his leadership abilities. He was transferred to 3/7th Battalion in October 1915, before taking his discharge at the expiration of his engagement in May 1916. He left with an ‘Exemplary’ character rating, the best rate there was.

Detail from Fred Patrick's first enlistment in 1909 (WO 364/2871)

In the early part of the war, before the application of the provisions of the Military Service Act of 1916, which brought in General Conscription, this was the right of Regular and Territorial Force soldiers whose period of engagement had been fulfilled. However, after the Military Service Act was implemented, those discharged soldiers who were still within the required age range and were still fit to enlist were recalled to the Colours, and this happened to Fred Patrick after only a couple of months at home. Although he was able to re-enlist into his old battalion, he was issued with a new service number, and because the structure of the Territorial Force had changed since the outbreak of the war, to create, in many cases, three battalions from one, he was enlisted into the 7th Battalion and Posted to the 1/7th Battalion, which was, in effect, the same battalion he had left only a few months earlier.

Detail from Fred Patrick's second enlistment in 1916 (WO 364/2871)

He was quickly restored to his former rank, and two months after being called up, he was sent back to France to join his battalion, which in October 1916 was in urgent need of Non-Commissioned Officers, especially experienced ones, to make good the losses the battalion had suffered in the fighting in the Battle of the Somme that summer.

Fred Patrick’s service record shows that after only 23 days back in France, he was evacuated to England, ‘Sick’, and was transferred to 3/7th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, which became 7th (Reserve) Battalion, and was based at Clipstone Camp in Nottinghamshire, where his health continued to deteriorate until three months after coming back from France, he was discharged from the Army. He was suffering from Tuberculosis and could not soldier on in any capacity.

The War Office provided a mechanism whereby soldiers who were discharged from service due to wounds or sickness could claim a pension, and those who did submit such a claim were sent for medical examinations to assess their condition and eligibility for pension awards. By May 1918, Fred Patrick’s condition had deteriorated so much that the examining officer reported that he was totally incapacitated, and it was suggested that he be admitted to a sanatorium for treatment. He had been awarded an immediate pension on his discharge from the army, but this was only an interim arrangement for six months until a more informed prognosis could be gained through monitoring and reviewing his condition.

Disablement Pension Award Sheet showing Fred Patrick's diagnosis of Tuberculosis (WO 364/2871)

After receiving treatment at the Leeds Tuberculosis Dispensary, to no effect, he was admitted to Seacroft Hospital, to the east of Leeds. The hospital had been built in the first decade of the twentieth century and had been specifically designed to be an infectious diseases hospital. The wards were built on raised brick pylons to allow full circulation of air all around them, and the corridors which connected the wards were open at the sides, with only a roof to provide shelter from the weather. It had a dedicated water supply and storage of water was obtained with a water tower, which doubled up as a clock tower. The hospital had been taken over for military use during the Great War, and with Killingbeck Hospital a few hundred metres away, across the main York Road, operated as a satellite hospital for the East Leeds War Hospital, now St James’s Hospital, on Beckett Street in Harehills. At the end of the war, the hospitals were handed back to the civil authorities, but a military presence was retained in each to provided assessment and treatment facilities for former service personnel who were in the process of claiming pensions or were receiving treatment as directed by the Pensions Board.

After becoming depressed with his condition, he was now confined to bed and unable to move independently, Fred Patrick cut his throat with his own razor during 8th February 1919. A doctor, Dr Gebbie, was on the ward at the time attending to another patient when he heard noises coming from the direction of Fred Patrick’s bed. The doctor went to his aid, but Patrick had inflicted four wounds to his throat, although no vital organs had been injured. Fred Patrick did not die of the wounds, but his doctor was sure that blood loss from the incident had hastened his death. At the inquest into the death, Dr Gebbie confirmed that Fred Patrick was depressed before telling the coroner that Patrick had said before he died that he had cut his throat as he felt he would be less trouble if he were dead, but that he was sorry he had done it.

What Doctor Gebbie told the inquest next is of the utmost significance and is important for two reasons. He informed the coroner that the cause of the death of Fred Patrick was pulmonary tuberculosis, accelerated by haemorrhage. The first reason why it is significant is that suicide was illegal until 1961, and those who succeeded in their bid to end their own life were referred to in the same terms as criminals, and those who failed in their suicide attempt were invariably arrested and put through the criminal justice system, incurring heavy fines or imprisonment as punishment for trying to take their own lives. Few people who, in the course of their professional duties, came into contact with people who suffered with suicidal ideation properly understood that they needed, and would probably respond better to, treatment, support and help, rather than punishment and the stigma that society would cast upon them. For a doctor like Doctor Nicolas Gebbie, a former captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps, with experience of war time doctoring, and the stresses and strains war put on the people who fought it, to see beyond the criminal aspect of a man’s suicide to give a fuller, perhaps more sympathetic and sensitive, explanation as to why his patient had taken his own life, shows that he was a man of understanding and empathy, not only to the dead patient, but to his family also. At the time, because suicide was a crime, even planning for the dead person to have a decent funeral could be a task fraught with humiliation and disdain from those who would be asked to officiate. What Doctor Gebbie said about how Fred Patrick died would shield his remaining family from that stigma and the judgement and condemnation.

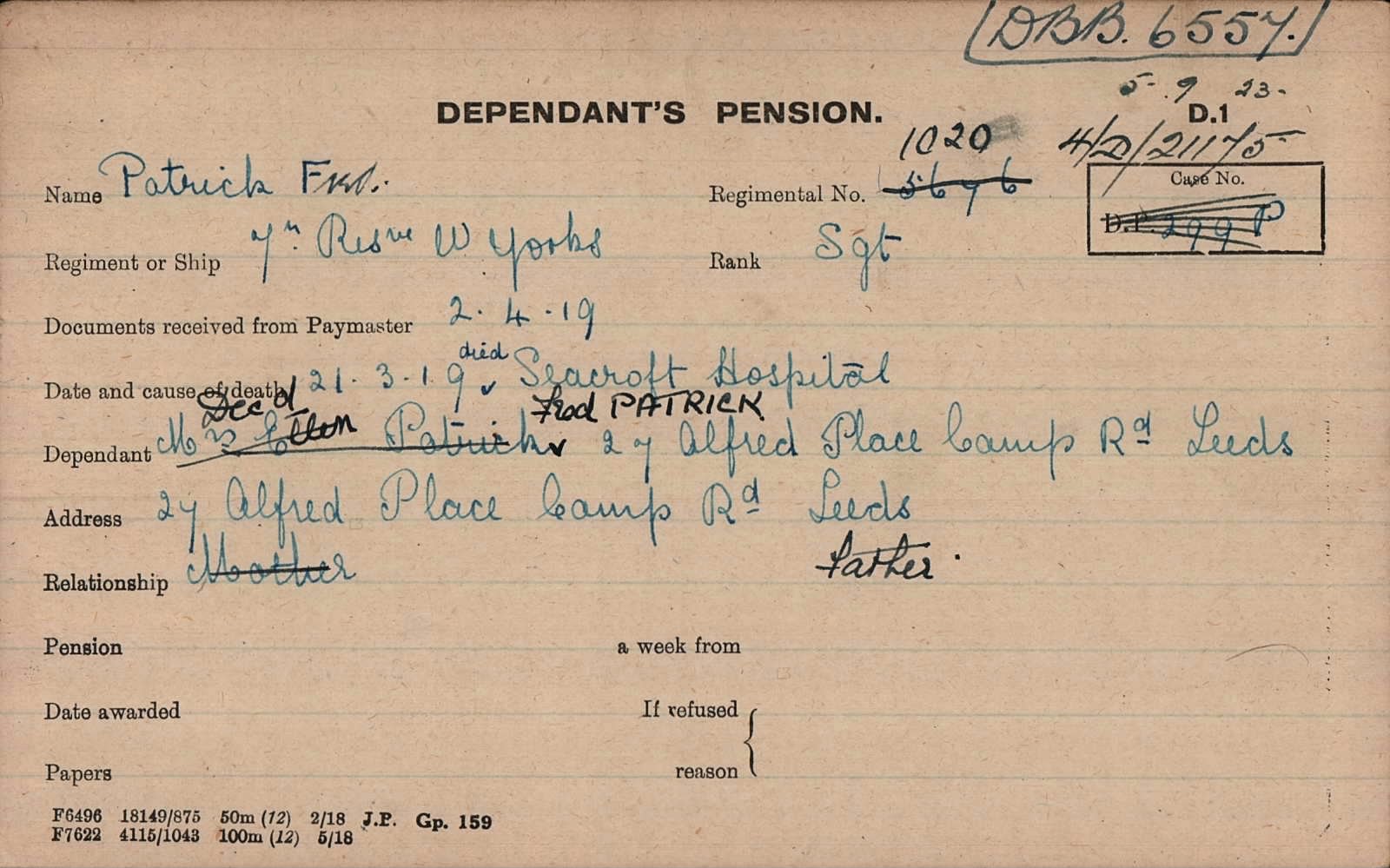

Dependant's Pension Record Card created following the death of Fred Patrick (Western Front Association)

Doctor Gebbie’s words are also important because after Fred Patrick died, he should have been commemorated by the organisation we now know as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, but 102 years after his death, he does not have that status. It is likely that something as simple as a clerical error stopped the paperwork being passed through the correct route and resulted in Fred Patrick not being recognised as a casualty of war for more than a century. This can now be rectified, thanks largely to Doctor Gebbie recording the death as being due to tuberculosis rather than suicide*. The rules that the Commonwealth War Graves Commission use to decided who may, or may not, be granted war graves status are relatively strict, but clearly defined.

For a soldier discharged through ill-health, such as Fred Patrick was, death must be caused by the same condition that was responsible for his discharge. The death must also have occurred between 4th August 1914 and 31st August 1921. Fred Patrick’s death, on 21st March 1919 is clearly within this period, and because Dr Gebbie recorded the death as being caused by tuberculosis as the primary cause of death, this satisfies the rule as it relates to discharged soldiers.

Map showing Seacroft and Killingbeck Hospitals (National Library of Scotland)

The prove to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s satisfaction that Fred Patrick’s death meets the established criteria, it will be necessary to provide them with Patrick’s death certificate showing the officially recorded cause of death, and appropriate military documents which show the reason for his discharge. Once both of those requirements are satisfactorily met, a case for recognition may be submitted to the Commission for their consideration.

When the Commonwealth War Graves Commission receives a new submission, the evidence that accompanies it is sifted to ensure that there is a prima facie case for them to pass on to the Ministry of Defence for a detailed examination of the case. In recent years, the Ministry of Defence has passed this examination work on to the National Army Museum which conducts any further investigation that may be required. The case is then passed back to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission with the findings of the investigation and a recommendation from the Ministry of Defence that supports a new commemoration or advises against one. The final decision is then made by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The process is slow, and most cases take an average of two years to complete.

*It is important to note that suicide has never been a bar to a casualty receiving war graves status and commemoration from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The policy of the Commission is to treat each casualty of war equally, regardless of rank, nationality, religious belief, or cause of death. To that end, it is normal to find officers buried next to private soldiers in CWGC cemeteries, as it is to find soldiers of all religious denominations, and none, buried alongside each other, and soldiers who are known to have died through suicide or those executed for military crimes are buried in military cemeteries without any distinction being made between them and those of their contemporaries who were killed in battle.

Dr Nicolas Gebbie qualified as a Doctor from the University of Glasgow. The following biography is taken from the university’s First World War Roll of Honour found at:

https://www.universitystory.gla.ac.uk/ww1-biography/?id=211

“Nicolas Gebbie was born on the 16th January 1889 in Govan, Glasgow, Lanarkshire, son of Henry (1855-1926) and Isabella Gebbie (1855-1924), nee Mair, living at 448 Crown Street, Govan, Glasgow, Lanarkshire in 1891. Nicolas went to Hutchesons' Grammar School before attending Glasgow University, where he graduated MB ChB in 1910.

In 1911, Nicolas was working as a Junior House Surgeon at the Borough Hospital, Park Road, North, Birkenhead, Cheshire, England, before moving to the Infectious Diseases Hospital in Leeds. In 1913, Nicolas attained a Diploma in Public Health from the Victoria University of Manchester. During this time Nicolas joined the Territorials and when war broke out, he was called up to serve. Nicolas was promoted to Lieutenant in the London Sanitary Company of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) on the 21st May 1916, and went to France in November 1916 and was promoted from Lieutenant to Captain in December 1916. Captain Gebbie was Mentioned in Despatches (MID) and awarded the oak-leaves for meritorious duties.

After the war, his thesis Artificial Pneumothorax in the Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis, with Special Reference to the Selection of Suitable Cases was published by the University of Glasgow in 1920. Nicolas married Helen Young Murdoch, MA, MB ChB, in Glasgow on the 28th September 1920. In 1930, Nicolas was awarded a Diploma in Psychological Medicine from the University of Glasgow and became a Medical Officer of Health in Hull, England. In 1935 he published a joint paper entitled Diphtheria.

Nicolas Gebbie died on the 21st May 1973, aged 84, in Holderness, Yorkshire, England.”