John Crawshaw Raynes VC - A Life of Service to Others

36830 Acting Sergeant John Crawshaw Raynes VC, A Battery, LXXI Brigade,

15th (Scottish) Division, Royal Field Artillery

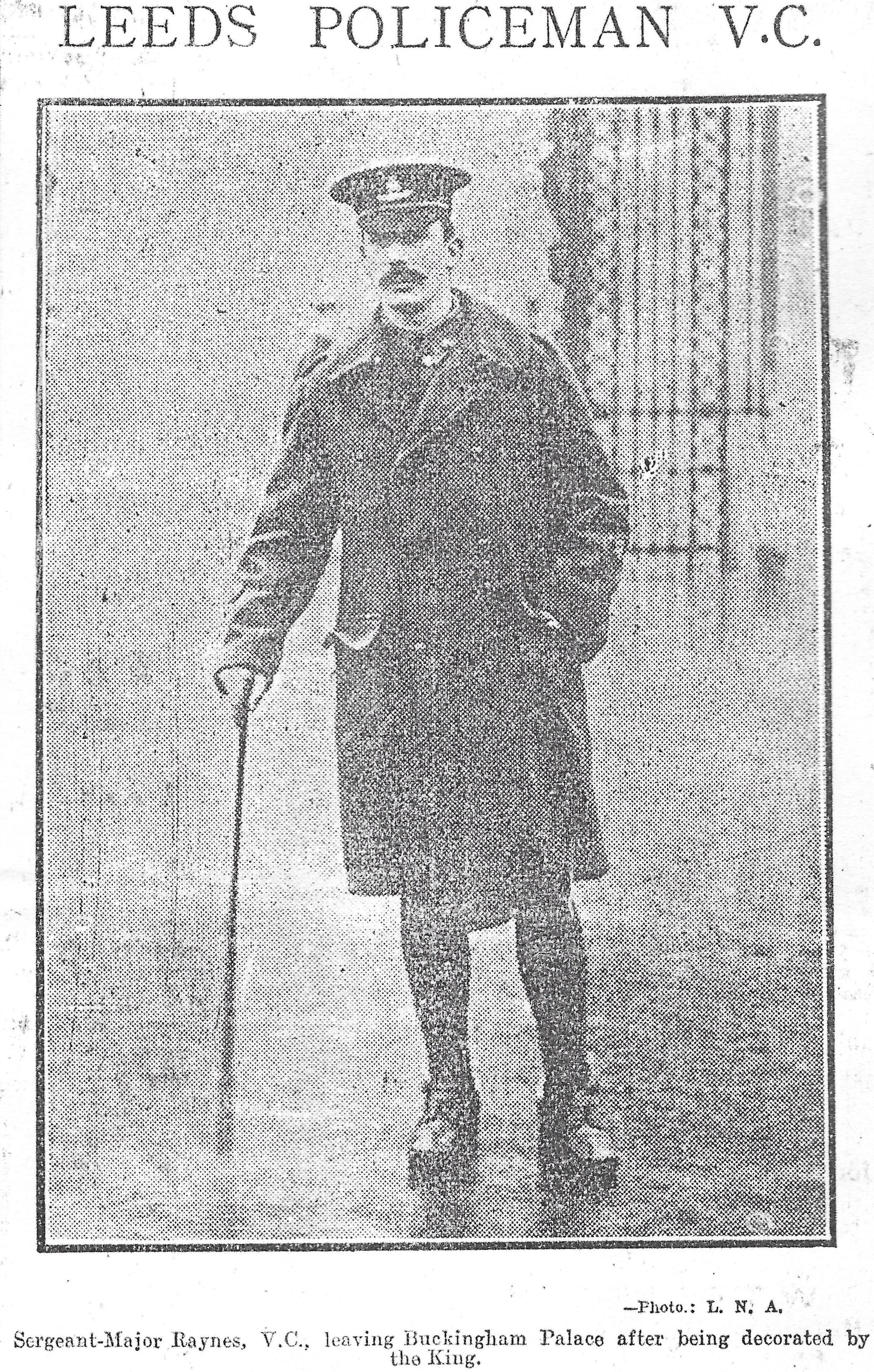

BSM JC Raynes VC following his investiture with the VC (Yorkshire Evening News)

Fourteen months after the outbreak of the Great War, a man from Sheffield, who had made his home in Leeds, performed separate feats of self-sacrificing bravery mid-way between Mazingarbe and Loos-en-Gohelle in Northern France that would be rewarded by the award of a Victoria Cross.

On 11th October 1915, Sgt Raynes’ unit, A Battery, LXXI Brigade RFA, was firing wire cutting fire missions in support of 15th Division operations in the final days of the Battle of Loos, the largest offensive action by the British Army during 1915. There had been some early gains by the British, but by October many of those gains had been recaptured by the Germans. The four guns of the battery were firing from a position marked on British maps as Fosse No. 7 de Bethune, which is immediately south west of the main Béthune to Lens road, near Mazingarbe and Vermelles. The position offered the battery visual cover from direct observation as it was behind the apex of the gentle rise out of Mazingarbe, and the guns positions were in the pit at Fosse 7. That is not, however, to say that the battery was safe from enemy shelling. Aerial reconnaissance had been carried out by German aircraft, and the battery’s position was accurately located by them.

While the whole of LXXI Brigade fired on German front line positions just south of Hulluch, the German artillery began counter battery work and a direct hit on the position of A Battery amid a ferocious bombardment using anti-armour shells combined with gas shells. The battery was forced to ‘Cease Fire’ while the numerous casualties were located and taken care of. Sgt Raynes had been sheltering in a dugout with his friend, Sgt John ‘Jack’ Ayres, when Sgt Ayres remembered that one of the battery guns had been left loaded when the ‘Cease Fire’ was ordered. Fearing a breech explosion, which would have destroyed the gun, and probably killed or wounded more men, he left cover and ran across open ground to the gun to clear its bore. He was successful in removing the shell from the breech of the gun and had just turned to make his way back to the dug-out when he was hit by a shell fragment. Having seen what had happened to his friend, Sgt Raynes broke cover and ran to the wounded Sgt John Ayres some forty yards from his own position and immediately set about binding up his wounds until the battery was ordered to resume its fire-mission. When the guns were ordered back into action, Sgt Raynes had to leave Jack Ayres, but as he left, he said ‘Cheer up, Jack, you’ll be in dear old England before me’.

Fosse 7 de Bethune (National Library of Scotland)

The battery was once more ordered to ‘Cease Fire’ due to the intensity of the enemy bombardment on its position, and remembering Sgt Ayres, Sgt Raynes called for two Gunners to help him bring Sgt Ayres into cover where he could be better looked after. Both the Gunners were killed by enemy shellfire, leaving Sgt Raynes to bring Sgt Ayres into a dug-out unaided.

When a gas shell detonated at the mouth of the dug-out, Sgt Raynes ran back to his gun to retrieve his own gas helmet, returning to the dug-out to use it on Sgt Ayres, which left him without any form of anti-gas protection, and as a result, Sgt Raynes was severely affected by the gas. Orders from the Commander of the Divisional Artillery Staff had stated that all men would wear their gas-helmets underneath their caps and would roll up the gas helmet until it was required. It appears that both the sergeants had lost theirs due to the proximity of the shell blasts. Five men were killed in the bombardment, and a further three were wounded, and so when the order was given to resume firing, Sgt Raynes, rather than seek medical aid, staggered back to serve his gun. Sgt John Ayres is counted among the men who died.

Later, the men withdrew to a street of houses, that ran parallel to the main road, called Quality Street. On the next day, 12th October, a heavy shell took down a house in which men were sheltering, trapping eight men inside. The first man rescued was Sgt Raynes, who was still suffering from the effects of the gas but was also now wounded in the head and one of his legs. He could have, perhaps should have, sought help for his injuries, but instead he preferred to assist the rescue party and remained to help to dig out all seven of the other men who had been trapped in the house, and the cellar. Only after the last man was brought out did Sgt Raynes retire to the advanced dressing station, just behind the battery emplacement, to have his wounds dressed. Instead of staying at the dressing station to await evacuation, he immediately reported back to his battery commander and went back on duty with his gun in the midst of another heavy bombardment.

For his actions during those two days, Sgt John Raynes would be awarded the Victoria Cross. Quite literally, his life would never be the same again.

On 13th October, he was appointed to be Acting Battery Sergeant Major, but with the effects of the gas, and his wounds, he was forced to be evacuated from the battery and before very long, he was in hospital in England receiving treatment. He relinquished his acting BSM appointment on 7th December.

The Victoria Cross to Sergeant Raynes was one of 18 announced in the London Gazette published on 18th November 1915. Most of the awards were for the recent Battle of Loos, but there was also one dating back to August the previous year for L/Cpl Wyatt of the Coldstream Guards.

The Victoria Cross (Dix Noonan Webb, London)

Naturally, the newspapers in Sheffield, where John Raynes was born, and Leeds, where he had lived and worked before the war came, were keen to tell his story, especially as he was the first VC associated with either city during the war. A reporter from the Sheffield Daily Telegraph did manage to get a few minutes with him for a piece which appeared in print on 22nd November 1915. When questioned about what he had done to be recommended for the award, Raynes answered in the same modest manner common to many who received the medal. He said, “I have only a hazy idea of actually what did happen, and I naturally wish to forget the whole affair. I simply did what other men would have done in similar circumstances. It was the biggest surprise in the world when I got a telegram congratulating me.” A few days earlier, he had told the newspaper that he had told his family nothing about the possibility of him receiving an award.

John Raynes received orders to attend Buckingham Palace on the morning of 4th December 1915, where he would receive the Victoria Cross from the hand of King George V in the Palace’s Ballroom.

John and Mabel Raynes with their son John Kenneth Raynes (Yorkshire Evening Post)

Despite his wounds, and the lingering effects of the gas, Sergeant Raynes was able to soldier on, however, he was not fit for front-line service any longer. On 1st February 1916, he was posted to 1B Reserve Brigade, RFA, based at Forest Row, south east of East Grinstead in Sussex, where he worked as an instructor. After just three months in this role, he was promoted to Battery Sergeant Major once more, and posted to Edinburgh with 6B Reserve Brigade, RFA.

In February 1917, he was posted to 393 Battery, RFA, an independent battery based at Westbere, near Canterbury in Kent. Five months later, in July 1917, he was posted to Southern Army Recruits Training Centre, attached to 1207 (Home Counties) Battery, a Territorial Force battery, where he remained until November 1917 when he was posted to No. 2 Royal Artillery Officer Cadet School at Maresfield Park, near Uckfield in Sussex. The park had been the property of a German Count before the war but had been confiscated by the British Government and turned over for use by the War Office as a training establishment.

Maresfield Park (National Library of Scotland)

Prior to John Raynes being posted to Maresfield Park, his

original army engagement expired. Earlier in the war, before the Military

Service Act was introduced in 1916, he could have left the army and returned

home, but with military service now being compulsory for eligible men, he was

compelled to remain in the Army, and his transition from one form of service to

another was marked by the payment of a bounty totalling £20.

After almost a year at Maresfield Park, Battery Sergeant Major Raynes VC was posted to 6C Reserve Brigade, RFA, a move which took him back to Edinburgh, however, this posting was likely to be an administrative exercise, as his health was in serious decline, and he was now too unwell to remain as a soldier, either at the front, or at home. Five weeks after being posted to 6C Reserve Brigade, on 11th December 1918, John Raynes was discharged from the Army due to his wounds and received a Silver War Badge. He returned to his family in Leeds, and, on 3rd January 1919, he returned to work for Leeds City Police Force.

John Crawshaw Raynes was born in Longley, to the north of Sheffield city centre, in South Yorkshire. Born on 28th April 1886, he was the eldest of four children in the family headed by Stephen Henry and Hannah Elizabeth Raynes. For much of his life, Stephen Raynes had been a publican, but in Later life he became a house painter, in which trade John Raynes began his working life.

It seems John Raynes had an interest in a military career from an early age, with his first enlistment being in the 1st West Riding Royal Engineers (Volunteers), based in the Drill hall on Glossop Road in Sheffield. On 3rd July 1903, he enlisted into the Royal Artillery, joining the Royal Garrison Artillery Militia in Norfolk Barracks, Clough Road, in the Highfield area. He left the Militia to join the Regular Army on 9th October 1904, but in a little over a year, he had been appointed Acting Bombardier.

At the age of 18-and-a-half, he joined the Royal Garrison Artillery at Burniston Barracks, just north of Scarborough, signing on for three years’ Regular Army service with nine years in the Reserve, although according to his Police joining record, he served for six years with 42nd Battery, Royal Field Artillery. The early part of his Regular Army service was spent in Leeds, with his battery being based at Chapeltown Barracks, but in April 1907, 42nd Battery moved to Coventry. At the same time as the battery move was being prepared, John Raynes married Mabel Dawson, a daughter of George Dawson, a groom whose family lived at Camp Road in Little London.

On leaving the Army, John Raynes returned to Leeds and applied to become a Police Constable in the Leeds City force. His application was successful, and he was confirmed in his appointment to A Division of the force as a 2nd Class Constable on 2nd June 1911, wearing collar number 102. A year later he was promoted to 1st Class Constable. He received a further promotion, and attendant pay increase in June 1914, when he moved into the three years’ service band of the force.

Police Sergeant John Raynes VC, Leeds City Police Force ( Sgt John Raynes, VC | Mig_R | Flickr )

In terms of his working life, John Raynes appears to have been successful in the Army, and he was certainly working his way towards being a successful police officer. Home life with Mabel was not so successful, and the couple had twice been visited by tragedy with the death, in infancy, of both of their children. There were two other children to the marriage, John Kenneth, born in 1912, and Tom Crawshaw, born in 1920.

When war came, John Raynes was still a member of the Army Reserve. He was liable for call-out under a General Mobilisation, but his status as a police constable exempted him from the training liabilities that most other reservists would have had. Over the course of the war, some 277 members of the Leeds City Police Force saw service in the Armed Forces, and of those, 29 were killed, or died because of their service. In response to the initial re-call of serving police officers to the Colours, the Leeds Watch Committee, the public body which over saw policing in the city, met to discuss its response. The committee decreed that police officers who were mobilised due to their Reserve liability, would be released without question, and their positions would be guaranteed on their return. In addition to this, any police officer who was recalled for military service would continue to accrue seniority in their current police rank to ensure that the military service they gave, over which they had no control, would not have any negative impact upon their police career. John Raynes was twice promoted to new pay scales in his absence during the war. When he returned to the force in January 1919, this continued accrual of seniority and no doubt, his Victoria Cross, ensured that the Watch Committee passed a special decree in his favour and he was promoted to Police Sergeant the very same day he returned to work.

Already, when he returned to the force, John Raynes was not a well man. He suffered lingering effects of his gassing, and his leg wound continued to trouble him. The police and the Watch Committee did all they could to accommodate his failing health. He was no longer able to supervise beat constables, and was given a station only job, but the deterioration in his spine prevented him from carrying out the role of a sergeant on duty at a station reception desk which involved standing for much of his shift. In time he was moved to an office job in the Aliens Registration Office, but in time, this role too became impossible for him and in March 1924, he felt obliged to resign from the Leeds City Police Force altogether after 13 years’ service. A mark of how long he had suffered, and forced himself to continue working, is seen in reports from the time of his funeral in 1929, which tell how he had spent the last four years of his life bedridden and crippled. This means that within months of his resignation, he was completely disabled and immobile. He had pushed himself far beyond any normal limits.

The Watch Committee met again to discuss what could be done to assist the Raynes family and approved an annual pension of £63 7s. 6d. It was noted that the house the family lived in at Lofthouse Place, Woodhouse, was unsuitable for the future because of the number of steps in the house, and that a more suitable house was recommended as an aid to Mrs Raynes, upon whom, John Raynes was entirely dependent, including his movement around the house, when she was obliged to carry him on her back. Eventually, following numerous appeals in the local press, particularly that by Sir Gervase Beckett, which raised £525, another house was arranged for the Raynes family to rent. The best that could be said about the house on Grange Crescent, where John Raynes would spend his final years, was that the street sloped slightly less than Lofthouse Place, and that there were fewer steps to climb to reach the house, but other than that, it was no more suitable for a man who was entirely unable to move unaided.

John Raynes was not forgotten in his plight, and he was regularly visited by former soldiers and colleagues from the Leeds Police. Despite not being one of their number, the Leeds Branch of the ‘Old Contemptibles Association’ kept in close touch with the family. John Raynes was recalled to the Army in August 1914, but did not proceed overseas until July 1915, having spent his previous wartime service as a signalling instructor in Preston. He had been offered a commission following favourable recommendations during his time in Preston, but he preferred to forego the commission in view of the delay this would cause in him going to the front.

On Saturday 9th November 1929, a dinner was held at the invitation of the Prince of Wales for all living VC recipients. It would be held in the Royal Gallery of the House of Lords and, of course, John Raynes was invited to travel to London to attend. He was unable to go, but his fellow Yorkshire VC recipients did not forget him, and a telegram extending their best wishes was sent to him for the gathering. A floral arrangement in the shape of a VC was brought back to Leeds from the dinner, with the intention of it being used to decorate the Raynes’ house in Grange Crescent, but before any of the returning VC recipients could visit his house, on 13th November 1929, John Raynes died. He was 42 years old.

John Raynes' coffin is borne into St Clement's Church (Leeds Mercury)

John Raynes VC, and his pitiful story were well known throughout Leeds. His death, leaving a wife and two young sons provoked an outpouring of sympathy from across the city.

A military funeral was arranged, and in the early afternoon of Saturday 16th November, his coffin, draped with the Union Flag was borne from his home by Artillerymen and placed on a gun carriage, provided by 69th Brigade Royal Artillery based in Leeds. Flanked by eight Leeds VC recipients, and followed by more, the funeral cortege conveyed the dead hero to St Clement’s Church, a mile away on Chapeltown Road. Captain William Ernest James Gage, formerly of the Rifle Brigade, the Chairman of the Leeds Old Contemptibles Association followed the coffin with Sergeant Major Raynes’ medals on a purple cushion. A detachment of soldiers from the Leeds Rifles, who would later provide the firing party at the cemetery stepped off with Arms Reversed, and a detachment of police officers led by their Chief Constable marched behind the carriage and Capt Gage.

The Leeds VCs escort John Raynes' coffin into the church (Leeds Mercury)

The route to St Clement’s Church was thickly lined on both sides of the road, and the crowds stood in silence as the cortege passed them by, men bareheaded in defiance of the rain. It was as if the entire city had turned out to give a final salute to their first VC of the Great War.

Following the church service, the funeral procession, bound for Harehills Cemetery made its way on the two-mile journey through streets still thickly lined with mourners, and when the funeral party reached the cemetery, the gates had to be closed behind it as the cemetery was awash with crowds thought to be approaching 30,000 in addition to the estimated 100,000 lining the route, all wishing to pay tribute to John Crawshaw Raynes.

As the gun carriage drew up near the burial plot, the VC recipients filed out to stand in vigil over the grave. They were Capt George Sanders, Lt Wilf Edwards, Sgts Fred McNess, Charles Hull (himself a serving police sergeant) and Albert Mountain, L/Cpl Fred Dobson and Ptes Arthur Poulter and William Butler, all of Leeds, with support from Capt Sam Meekosha of Bradford, Sgt John Ormsby of Dewsbury and Cpl Albert Shepherd of Royston, near Barnsley.

John Raynes' coffin is brought to the burial plot, with the Leeds VCs keeping vigil at the graveside (Leeds Mercury)

Mrs Raynes was helped to and from the grave by her elder son, Kenneth, while the younger boy, nine-year-old Tommy, was escorted by retired police inspector, Mr Heath, a long-standing family friend. The only sounds to be heard in between the words of the officiating clergy, Reverends Shuttleworth and Duffield, were those of falling rain and a restless horse’s hoof on cobble sets.

The firing party and buglers from the Leeds Rifles brought the ceremony to a conclusion.

Four years after his father’s funeral, the now twenty-year old John Kenneth Raynes was sworn as a Constable into the Leeds City Police on 6th January 1933. He would serve a full career, interrupted only by his service during the Second World War. When Kenneth Raynes married Margaret Fergusson in October 1941 at Scarborough, the marriage was conducted by Squadron Leader the Reverend Chaplain Arthur Proctor VC. Like his father, Proctor had received his decoration for rescuing wounded men, when in June 1916, near Ficheux, he spotted two wounded men laying in full view of a German trench. Like John Raynes’ VC action, that of Proctor was a two-part rescue, with the first part being to tend their wounds and pull them into cover, before returning for them once it got dark. In Proctor’s later life, there would also be a Sheffield connection created, as Arthur Proctor retired to the city in his final years. After his death and cremation Arthur Proctor’s ashes were interred in a vault in All Saints Chapel at Sheffield Cathedral.

For Mabel Raynes, the Second World War must have been a source of enormous worry as the mother of two sons in the Royal Air Force. She knew what it was like to lose a brother having lost hers, Private Tom Dawson, of the Highland Light Infantry who was killed a week before Christmas in 1914. She had seen how her husband had had his health destroyed by war and had done her best to nurse him through to the end of his life. In 1918, her husband’s brother was killed too, when L/Cpl Frank Raynes was killed fighting in Italy. The end of the European War in May 1945 must have come as a huge relief to her, knowing that both her sons had got through, even though her younger son, Tom, had contracted malaria while serving in the Gold Coast, now Ghana, in Africa.

With only a month left to serve before he would be demobilised, Tom Raynes, a Leading Aircraftman in the Royal Air Force had hitched a lift in a jeep as he tried to get home to Leeds to see his wife and daughter. He was killed when the jeep was involved in a crash a Blisworth, Northamptonshire. He died on 22nd August 1945, aged 25 years.

Eventually, after the death of Mabel Raynes, the Victoria Cross and medals awarded to Battery Sergeant Major John Crawshaw Raynes passed into the custody of their surviving son Kenneth and his wife Margaret, who kept the medals in a frame on the mantlepiece, in their home in Moortown, Leeds. Following Kenneth’s death in 1972, Mrs Raynes was concerned about having such a valuable object in her home, and following contact with the Royal Artillery, arrangements were made for Mrs Raynes to hand the medals over into the safe keeping of the Regimental Museum during a day where she would be guest of honour at a ceremonial reception for the VC.

Like many cemeteries across Leeds during the second half of the 20th century, neglect and vandalism were responsible for thousands of graves falling into disrepair, and while the grave of John Raynes offered no sport for the vandal due to it being a low-lying kerbed enclosure with a marble cross laid flat across the plot, it was neglected and somewhat deteriorated. In 2008, a serving police officer, PC Anthony Child, of West Yorkshire Police discovered the grave and was shocked by the state it was in. He obtained the support of the West Yorkshire Police Federation, and the Leeds Police Sports and Social Club and planned for the grave to be renovated. Later that year, after the work was completed, on the 79th anniversary of John Raynes’s death, a service of rededication was held at the graveside in Harehills Cemetery.

Sgt Jack Ayres

John Oswald Ayres was born in Worthing in Sussex on 16th February 1887. He was the second child of six for William and Lettie Ayres.

His background and route into A Battery, LXXI Brigade RFA could not have been more different to that of John Raynes. His first enlistment was into the Royal Navy, but he was discharged on 8th December 1904. His length of Service and reason for discharge have not been recorded. He next enlisted in the army, joining the Royal Sussex Regiment on 23rd February 1905, however, he was discharged on 16th May in the same year as ‘Service No Longer Required’. He then enlisted into the Royal Army Medical Corps Militia, but on 18th August 1905, he left enlist into the Royal Marines Light Infantry before transferring to the Royal Navy in December 1905. His time in the Royal Navy ended badly for him after he was convicted at court martial of striking a superior officer and using insulting language towards that same superior officer, and for those offences he was sentenced to 12 months imprisonment with hard labour, and subsequently dismissed.

Next, he enlisted into the Royal Horse Artillery on 2nd October 1908, but this enlistment, like his others, failed to last. It isn’t recorded when he was dismissed from the Army, but by 1st April 1909, he had already enlisted again into the Royal Navy and had been tried and imprisoned by the civil power, and on 28th April 1909, he was dismissed from the Royal Navy for giving a false account at his enlistment.

How the Illustrated Police News told the Story of John Raynes and Jack Ayres (Illustrated Police News)

His enlistment into the Army for service in the Great War appears not to have been of any concern for the Army, indeed, he was quickly promoted to Sergeant in command of a gun.

On the day he was wounded and subsequently died, Sgt Ayres had saved a gun from possible destruction by clearing its bore of a loaded and rammed shell. His action may have saved lives too. For his bravery in saving a gun, he was Mentioned in Despatches, however, because the only awards that could be given to men who had died in action for which they were being rewarded were the Mention in Despatches and the Victoria Cross, had he lived, he may well have received a Distinguished Conduct Medal for his bravery that day.

After his death on 11 October 1915, Jack Ayres was buried in what would become Fosse 7 Military Cemetery (Quality Street), Mazingarbe. Bombardier Dathan, and Gunners Bean, Houghton, and Humphries were buried with him, and their collective grave was marked and recorded, however, during the course of the war, the cemetery was damaged and afterwards, it was impossible to locate the marker that had been erected over the grave, although records confirmed the men were buried in that cemetery. This resulted in the men being commemorated by means of special memorials placed at the edge of the cemetery, while the actual graves bore headstones which commemorated an unknown soldier of the Great War. Research in 1960 confirmed the identities of the ‘unknown’ men in the collective grave, and from then on, their grave has borne named headstones.